Loops and Ligatures: The Calligraphy of Seb Lester

Where did you grow up, and how would you describe your childhood? Was creativity encouraged by your parents?

I grew up in Birmingham, England. Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath also hail from Birmingham. My parents always encouraged me to draw and paint, and they made sure I had pens, paint, and paper to do so.

How did you make the decision to go to an art and design school? Was it obvious that this would be your career path?

I generally did well in school, but when I was a kid, I wanted to be either a professional BMX rider or an artist. If I wasn’t on my bike, you could find me painting and drawing. Over time, art and design became my main focus. For as long as I can remember, creativity has been a very important part of my identity. Being an introvert, it has always been an essential form of self-expression for me.

Your early career focused on designing typefaces. When did you create your first? Did it happen organically?

I was in a foundation art course in Birmingham in 1992. I found myself gravitating toward letterforms and started drawing alphabets on graph paper. My early alphabets all looked like 1980s BMX logos because those were my main influence.

Calligraphy is a more recent addition to your art. How did that come about?

In early 2011, I felt like my career was really about to take off. I was working on a front cover for Creative Review, which any graphic designer knows is a pretty big deal. I was also working on a very big project for Nike and was lined up to speak in Australia at Semi-Permanent, a big design conference, later that year. Then, out of the blue, my partner, Pamela, was diagnosed with cancer. This was a big shock to both of us, and it turned our world upside down overnight. I walked away from all of those projects to take care of her.

There was no way I could do client work during this period. I could hardly switch on my computer, but what I could do was find time to doodle in sketchbooks. As Pamela’s condition slowly stabilized, I was able to spend longer periods of time writing and trying out different pens and ideas. Calligraphy was the only creative outlet I had at this point. Playing with words and letters became a very absorbing form of escapism—a respite from what was a very dark period in our lives. I had occasionally dabbled with calligraphy pens before, but I don’t think I would ever have found the time to learn calligraphy any other way.

Today, Pamela’s cancer is in remission, and she’s healthy. My career is back on track. Life is pretty good at the moment. For now, the sun shines again. I learned that you can get through really tough times if you hang in there. I was reminded that life is short at the best of times—it’s a fragile, fleeting experience that no one should take for granted. I try to make more time for projects that really matter to me now. I work hard, but I also have a greater appreciation for the good people and good things around me.

The experience brought Pamela and me closer together, and I came out of it being able to write some pretty fancy letters with a pen. Against the odds, the experience actually ended up making me a better designer and artist, perhaps even a better person. Whatever the future holds, that will always be a beautiful thing. Sometimes clouds do indeed have silver linings.

What does calligraphy offer you in terms of creative fulfillment that is different than a typeface or a logo?

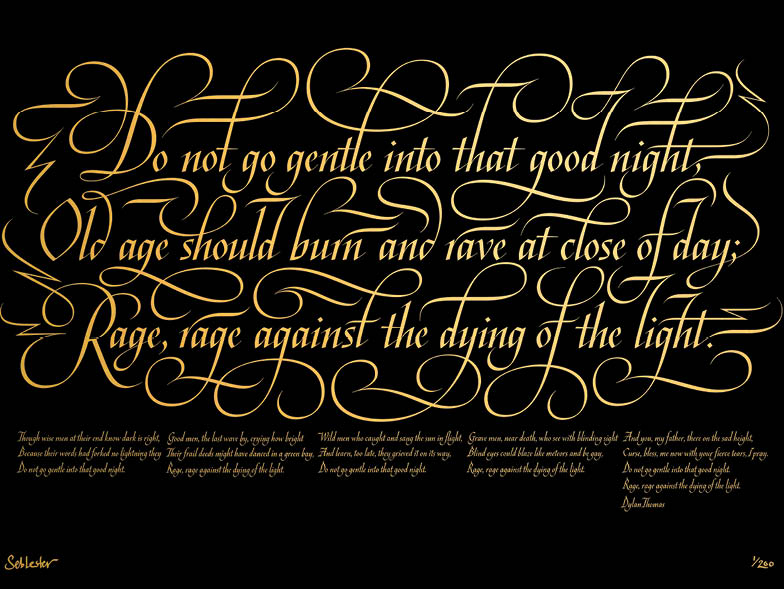

Almost all the calligraphy I do is either sketchbook work or a full-fledged art project, which leaves a lot more scope for personal expression and creative exploration. I am as interested in language and words as I am in their expression through calligraphy. A lot of my calligraphy juxtaposes modern sentiments, ideas, and language with ancient craftsmanship. That is part of its appeal—it feels fresh, modern, relevant, and accessible to a lot of people. The vast majority of my calligraphy is done very quickly and freely in sketchbooks. It is often a visual play with words and letters, and it’s often very sketchy and unfinished.

Calligraphy is a very emotional process for me—probably in part because of the reason I came to it. I put a lot of love into what I do, and I hope that comes across in the final pieces.

What has the transition been like from typeface designer to freelance artist and designer?

A lot of the typeface designs I have done have been corporate designs for big, multinational companies—airlines, banks, and huge retailers. Work like that has its rewards, but it also has inherent constraints. The work is generally very conservative, and there isn’t much scope for expression. In 2008, I started seeking out new challenges and pushing myself in different directions. I found it strange and unsatisfying that I was working so hard and seeing my work every day on TV and billboards, yet I was not getting much recognition at all. I started doing more expressive work with letterforms, limited-edition prints, and other personal projects. It was a counterbalance to the corporate day job. The personal projects generated a lot of interest, and it became clear that it was time to go out on my own. Upon reflection, I wish I had done it sooner.

Is it more difficult to make a living? Are commissions or personal work your primary source of income?

It is harder to make a living doing personal work at the moment because it’s speculative. Right now, almost all of my focus is on self-initiated art projects, mainly limited-edition prints, but also original pieces. I am offered a lot of client work, but I am being very selective. I obviously need to make a living, but I’m not motivated by money. I’m at the point in my life where I need to do projects that are important to me and push me to the limit of what I am capable of creatively. As a result, I hope it’s the kind of work that will endure. I take on maybe two or three client projects a year at the moment—the kind of projects I can’t say no to. My last two client projects have been a logo for a NASA space mission and some architectural lettering for Norman Foster.

Is it important for you to connect with the words you’re writing on a deeper level than just visually?

I try to find words that resonate with me and inspire me to interpret them visually. Calligraphy is a very powerful and seductive art form. I don’t accept the idea that calligraphy is a redundant anomaly in the twenty-first century—my last calligraphy video compilation had more than one hundred million views on Facebook. That didn’t happen because calligraphy is redundant and irrelevant; it happened because calligraphy is a beautiful, ancient magic. Its function in the twenty-first century has simply shifted from disseminating information to art, design, and recreation.

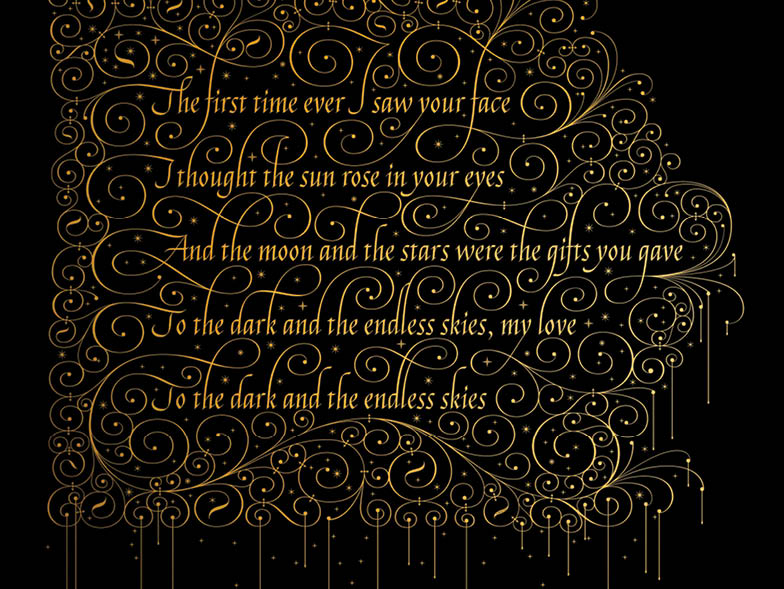

How does First Time Ever speak to you? Why did you choose the song to interpret into art?

That print is based on the song “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” which was written by Ewan MacColl. I took the trouble to license the lyrics because I think it’s quite simply one of the most perfectly formed love songs ever written. It’s a universal and eternal sentiment, and the language is so evocative I could instantly see how I wanted to interpret it in print.

Is there a moment you felt you “made it” in the design world?

When PBS NewsHour interviewed me about my work last year, it made me think things are going pretty well. I have also been invited to speak about my work all over the world in the last few years, from Australia to the Philippines to the United States.

With an ever-increasing audience, do your fulfillment and motivation come from bigger and more prestigious commissions? Do you feel affirmation through increasing fame, from a more personal place, or a bit of both?

The most fulfilling projects I do have all been self-initiated. It was amazing when I designed the corporate typeface for Intel, which ended up being used all over the world. But, at this point, I have been there and done that. Like I said, money isn’t my primary motivator. My motivation is to try to produce profoundly good, transcendent art—work that connects with, resonates with, and moves people.

You have a presence on Facebook and Instagram. What do you like about that interaction? Is it important for you to connect with your audience and fans?

I find social media to be overwhelming sometimes. I have 1.3 million people following me on social media. That is respectable for a pop star, let alone a nerd with a lot of pens. It’s great, and I wouldn’t want it any other way, but it does create pressure. My followers seem to come from every continent and every walk of life. One of the biggest achievements of my career is crossing over as a calligrapher to an artist with a mainstream audience that finds my work interesting. It is a humbling, surreal, and beautiful thing.

There’s this awesome juxtaposition between the poetic, philosophical excerpts you choose to make into calligraphic art, and then this irreverent side. Is this a reflection of your personality? Is it your way of staying grounded?

I take my art very seriously, but I don’t take myself too seriously. Despite some of the crazy things going on at the moment, my feet have remained firmly on the ground, and self-deprecating humor helps with that.

Do you still fight the feeling that your work isn’t good enough for your own standards? If so, do you think this feeling ever goes away? How do you push past it to keep designing?

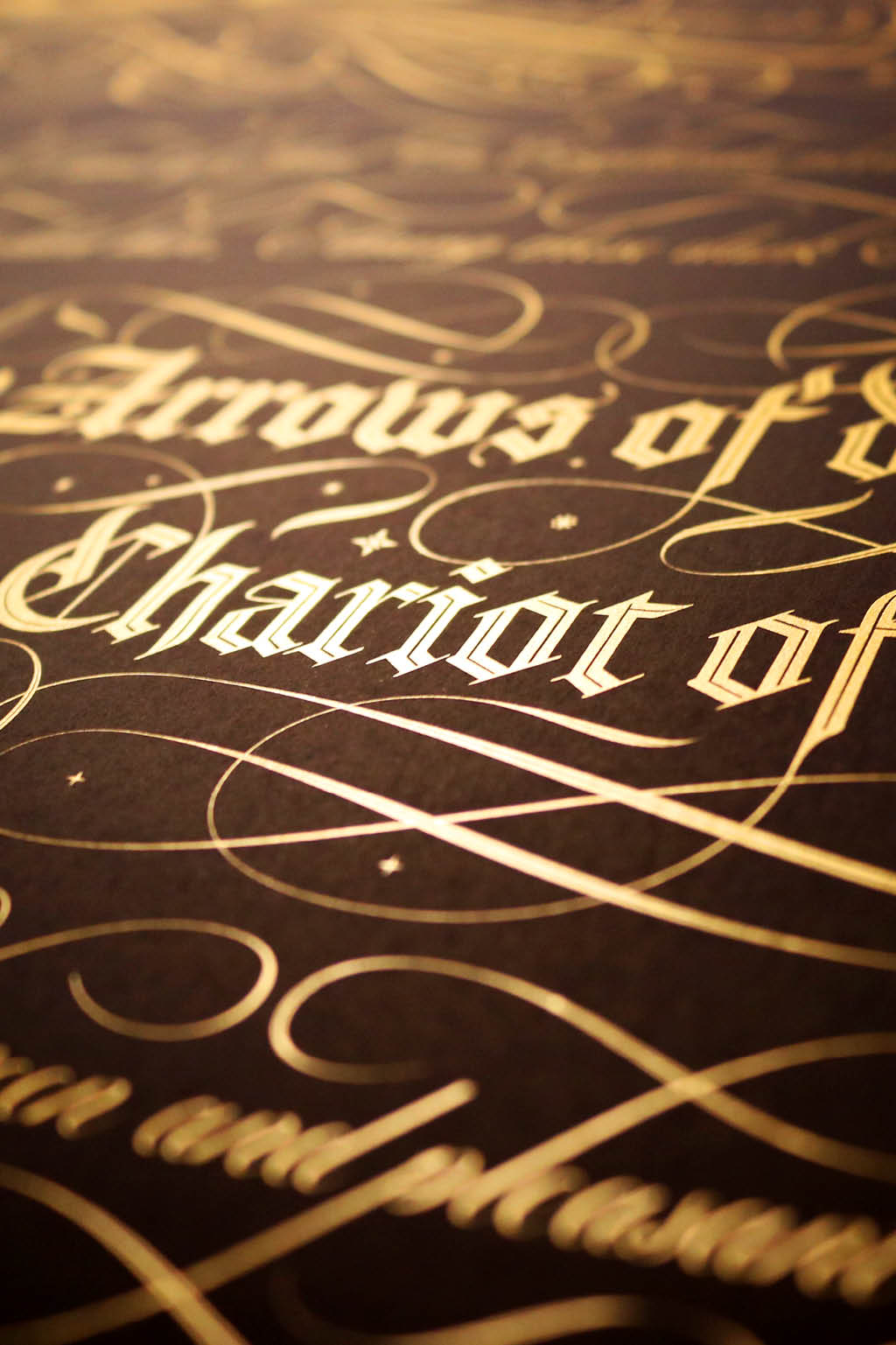

Almost every day, I feel self-doubt and a sense that I can do so much better. I have produced perhaps five pieces of work in my life with which I am very satisfied. One of them is my Jerusalem print, my tribute to the artist and poet William Blake. I’m also very proud of a typeface I developed called Neo Sans. But I see the flaws in my work first and ways in which I could have made things better. The more I learn, the more I understand how much I have to learn about letterforms.

Why does the county of East Sussex suit you?

We recently moved into a converted old stable. It’s built into the banks of one of the oldest castles in England. It’s a peaceful place, surrounded by nature, with an eleventh-century castle in the back garden. A couple of pet rabbits and a cat run around the place, and they’re great fun. After fifteen years in North London, it’s all a bit surreal, but I’m quickly getting used to it. Pamela had wanted us to move here for a long time, and her illness fast-tracked that process. We moved from London, but I was worried that my work would suffer moving to somewhere more rural. I thought I might have been feeding off the chaos and intensity of London, but I was wrong. Things have worked out very well.

Who or what inspires you?

I’m inspired by true virtuosity in the visual arts, particularly calligraphy and lettering, but also drawing and painting—calligraphers like John Stevens and Jean Larcher, lettering artists like David Smith, and painters like James Jean, David Kassan, and Serge Marshennikov.

What does your life look like outside your career?

“The trouble is, you think you have time” is a quote that really resonates with me. I need to make time to do the things that matter most to me, including making time for the important people in my life. So I spend what little spare time I have with Pamela and with my friends, family, and pets. I can also feel a lot of momentum gathering in my career at the moment—I’ve set some big goals for myself as an artist, and it will be interesting to see how my career develops over the next few years.

For more info, visit seblester.com.