The Call of the Brush: Artist Jeffrey Roth

After a career in the entertainment industry as an art director and an animator, artist Jeffery Roth turned his attention to watercolor painting full time, answering the call of a new passion and beginning his next chapter of creativity.

What is your earliest memory of making art?

My first memory of creating art goes back to my earliest memories of my life. I can still hear a distant muffle of grown-ups towering above me and calling my name—their voices muted by the depth of my singular concentration and my face inches away from the page.

What did the path to becoming an artist look like for you?

I’ve always thought I would be an artist. Having grown up in Carmel, California, I was always surrounded by artists—some world-famous, others locals who really understood the value and impact of art on a community. My biggest obstacle has always been the definition of art itself and how that defines one’s life.

Tell us about your career in the entertainment industry. How did that come about? How did that suit your personality?

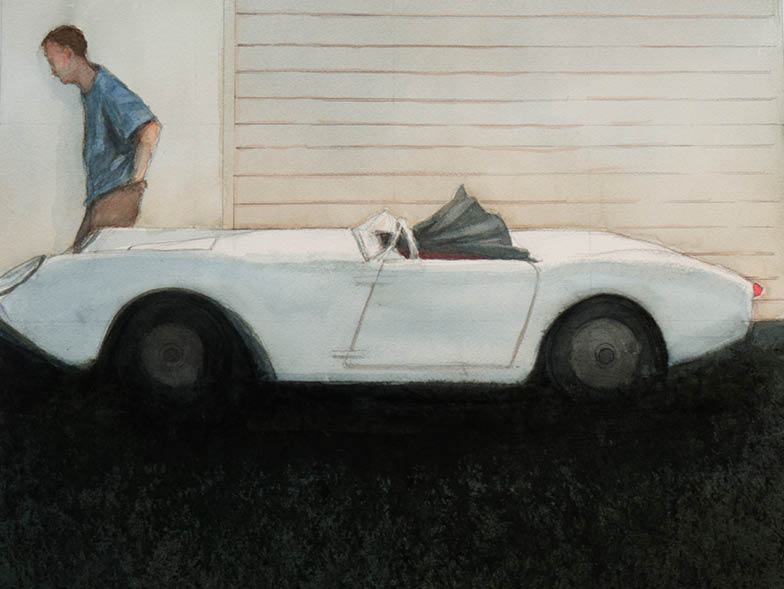

Art, cinema, and actors helped define the little oasis that is Carmel, and I was not immune to the allure. I had wanted to become a cinematographer. I wasn’t seduced by the idea of the director’s role; I’d wanted to be the person who designs the illusion, the seduction of cinema, and its ability to create an environment that allows complete suspension of disbelief.

When I was in art school, I had a chance to work at a Macworld/iWorld show in San Francisco. At the time, this was an extremely exciting moment in the convergence of art and technology. Digital tablets were just a burgeoning idea that would allow an artist to work on a pressure-sensitive tablet with the use of a special pencil input device. This could mimic the result of the analog world, allowing the simulation of brushes and pens on paper. Such a fantastic and novel idea was too great to pass up. I was told to simply “draw” and do my thing. So I would sit in a chair with the tablet on my lap and my eyes staring up at a monitor, sketching away whatever images I would conjure in the moment. A group of men stood for over thirty minutes watching me work, saying nothing. After a short time, they returned, and one of them handed me a business card and said, “Come here on Monday and you’ll have a job.”

It was that simple, that fortunate, and that magical. My job was at a company that was in its own creative nexus. They had access to all kinds of mediums. This was a creative powerhouse, and I was allowed to “play” and create ideas and key frame art, which is the visual reference made during the initial creative phases of production. I went on to work as an art director and animator for such production houses as DreamWorks Animation, until I decided to become a freelance artist and cherry-pick the right projects.

I never stopped making art by hand, though, whether it was sculpture or the constant presence of my sketchbook. I have had the great privilege of working with some of the best directors of our time but came to realize that I wanted to contribute something more intimate and personal, and I could no longer deny my growing passion for watercolors and the challenges that each work presents—as much drama as a film production, but complete control from the first brushstroke to the last.

Have you always lived in California? What is the energy of the place?

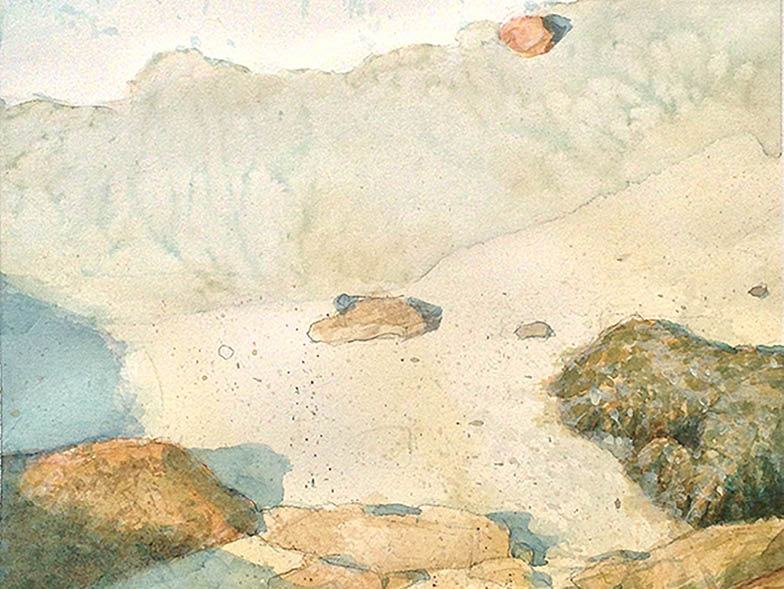

I’ve spent most of my life in California and always lived near water—a year on the

big island of Hawaii and a year in Boston for school. The power of water has always seduced me and has always been a part of where I live. From the complete sensory experience of sight, sound, and smell, it’s really an undeniable force that deserves reverence and endless observation and demands humility and respect.

Do you consider yourself an artist first?

I couldn’t define myself as anything but an artist. It is simply who I am, and it informs all of my other manifestations.

What is a word of praise or criticism that stands out to you?

One of my teachers in art school, named Brook Temple, had a profound effect on me. He wasn’t impressed with my skills, and he made that very clear. This made him unique; he knew that he had a much deeper understanding of the questions I should be asking.

When I was finally beginning to understand some of this message, he said to me, observing my new confidence, “When you feel like your work is getting good, take it and set it next to a Picasso, a Degas, or any of the great ones, and ask yourself, ‘Is this work worthy to be called masterful?’”

That really hit home, because the accolades and awards I had just received for my work suddenly lost their luster and my sights were quickly adjusted. That’s a litmus test I still use to this day, and I’ve yet to match that standard—but I refuse to stop trying.

What do you hope an audience will perceive or feel when looking at your work?

For me, creating art is still a sacred act, a pure thing with the same focus and curiosity of a child. I seek the beauty and poetry of a single moment. Triggering those memories in others’ minds, some so great they can remember exquisite details such as smells and tastes and feelings—that’s what I’m striving for.

Do you have a mission statement or words you live by?

I know that “Be here now” is a California cliché, but the idea is a noble one that requires concentration and observation in the moment. This is a rather elusive skill in these times of quick-paced access to an overabundance of information inundating all our senses.

How would you describe the style of your work?

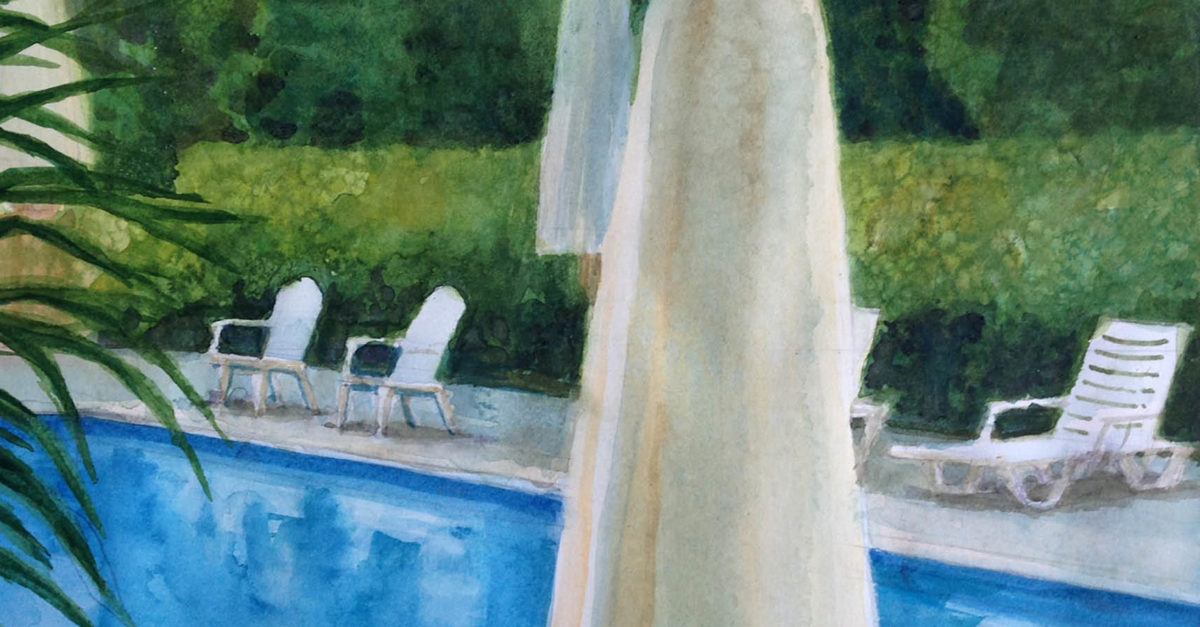

I strive to create an experience or escape for the viewer, whether that’s an internal voyage or an external one. To coin a phrase, I would call it “cinematic realism,” since cinema is an opportunity to create an illusion that the viewer wants to journey through.

What is your preferred medium?

I love to create, so I try not to box myself into a corner, but I paint watercolors now more than anything else. I also love the colors and viscosity of oil paints, and I enjoy creating some sculptures, but I find the immediacy of watercolors to be an extraordinary challenge.

How do you choose a subject? What does your process look like for creating a piece?

For me, the image must touch me, if not take my breath away. I often begin with a sketch or a photograph. I have simple rules: I must have experienced it myself, I will only use photos as reference, they must have come from my own creation, and, with any luck at all, they must elicit that moment of wonder. Once I begin, I must complete as much of it as possible in a single sitting. I find that the flow and energy of the dance is gone if left too long.

Do you get frustrated with paintings? How do you handle that tension?

One of my teachers at art school would ask if he could sit down for a moment at my drawing bench. This was often followed by him taking a large piece of charcoal or whatever drawing medium I was using to completely obliterate my image. He would stand up, smile, hand me the charcoal back (while saying “There!”), and walk away. He later revealed the lesson that I should never get too attached to my work.

What advice would you give to a beginning painter?

I have often given this advice in the past to those who want to go down this path: just create. Don’t try to make art—just enjoy the experience that it brings to the heart and mind. Later, if you take stock of what that journey really entails, seek out someone with years more experience. Get the tricks and techniques you will need, but enjoy the raw, pure joy of creation, and find a mentor to fill in your gaps.

Who are you influenced by?

There are the giants, like the Renaissance masters, who still thrill me. There are the masters of light, like Caravaggio, Sorolla, Monet, and Matisse; the draftsmen like Michelangelo, Sargent, Diebenkorn, and Picasso; Rodin for form and poetry; and my personal mentors—Donald Teague, for one, who spoke with me little of technique and mostly of the power of art.

Will you share a lesser-known fact about yourself?

Since high school, I have been studying a rare and exotic form of Chinese martial arts called bagua qigong, which I have recently started to teach. It is much like tai chi chuan, but more active and fluid, like water. Again, there’s that water thing.

In the alternate reality movie of your life, where would you be living and what job would you have?

I have often used a one-line joke when things become complicated: “I should have stayed in Hawaii and grown orchids.” Still a fine plan if this one doesn’t work out.

For more info, visit www.jefferyrothpaintings.com.