Names Worth Saving

She knew it, and they knew it. The destruction of the house would be a heartbreaking loss. But the work Hildie Carney and her four fellow preservation-minded neighbors in Fairfax, Virginia—Brad Preiss, Bill Jayne, Andrea Loewenwarter, and Fairfax mayor David Meyer—were about to take on was a far greater commitment than a few weekends, and time was not on their side.

For over a year, beginning in late 1997, they met a couple days a week in Carney’s basement with a goal to save a nearby residence known as Blenheim. The home’s most remarkable feature, a Civil War treasure in what was once Confederate territory, was untouched for 137 years: graffiti left by Union soldiers on the attic walls. Carney and her neighbors didn’t know it at the time, but other walls in the house contained their own hidden stories.

The owner, Bill Scott, died earlier in 1997. His wife, Barbara, the last direct descendant of this historic property, had passed away ten years prior. In his later years, Bill could not afford to care for the twelve remaining acres of property on which the home was situated. (Blenheim’s heirs had sold off the majority of the land, once a vibrant agricultural landscape of 367 acres, for residential development in the 1950s.) As a result, the Greek Revival-style home, built around 1859 by Albert Willcoxon, was now shrouded by vegetation and “had a lot of trees and overgrown bushes,” Carney says. Only a narrow, dirt driveway—not the home, which was set two hundred feet back—was visible from the road.

Through her dining room window, Carney could take stock of the challenge ahead for her and her neighbors. She had moved here in 1964, and, thanks to her boys discovering Blenheim after venturing through the woods, she had met Barbara Scott. Over the years, Carney and Scott became close. Scott showed her the attic and expressed concern about what would happen to the house after she and her husband died, as they had no children.

The serenity of the Scotts’ years at Blenheim could not be further from the mayhem that befell the home in the early 1860s. Albert Willcoxon was the one hundred fifth male in Fairfax County to vote for secession. In July 1861, Union troops destroyed or occupied homes that belonged to secessionists on their way to the First Battle of Bull Run. It is believed that this is when the family took what it could and temporarily abandoned the home. By March of 1862, Fairfax became Union held; in September of 1863, Willcoxon signed an oath of allegiance to the United States, and he was allowed to return home with his family.

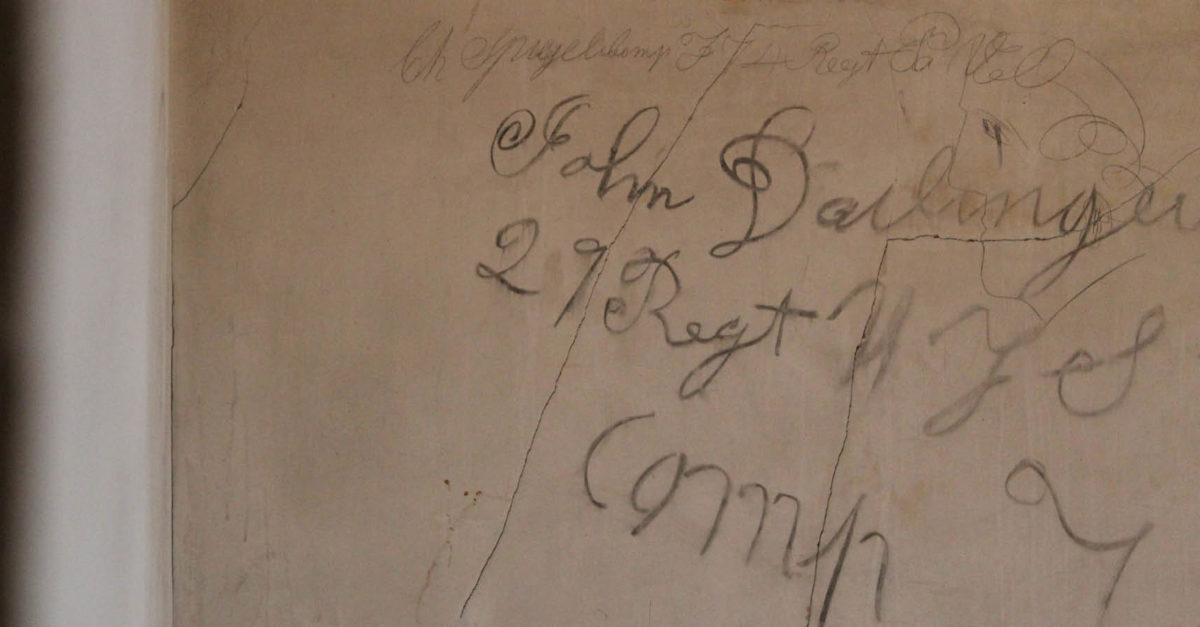

“Blenheim was built only a few years before the beginning of the Civil War, so there were these blank walls that the Willcoxons hadn’t painted because the plaster wasn’t dry. The Union soldiers were bored, chomping at the bit awaiting orders. Over a two-week period, 75 percent of the 122 identified names were written on the walls throughout the home, and then the soldiers were gone, on to their next assignment,” says Loewenwarter.

While other structures in Virginia have Civil War soldier graffiti, Blenheim has the state’s largest collection of identified and best-preserved soldiers’ signatures and well-protected pictographs and sayings, some cartoon-like. For example, Private Theodore Raefle decorated his inscription with a wreath and crown reminiscent of the coat of arms of his home in Prussia. Private Henry van Ewyck, a former sign-painter born in the Netherlands, wrote in precise, formal handwriting. Although far from water, there are several drawings of ships, including three elaborate ones in the attic. Most notable is an unsigned comic-strip-style series of vertical pictures that charts the progress of a soldier from a flag-waving civilian to a slouched, disillusioned figure after four months of service.

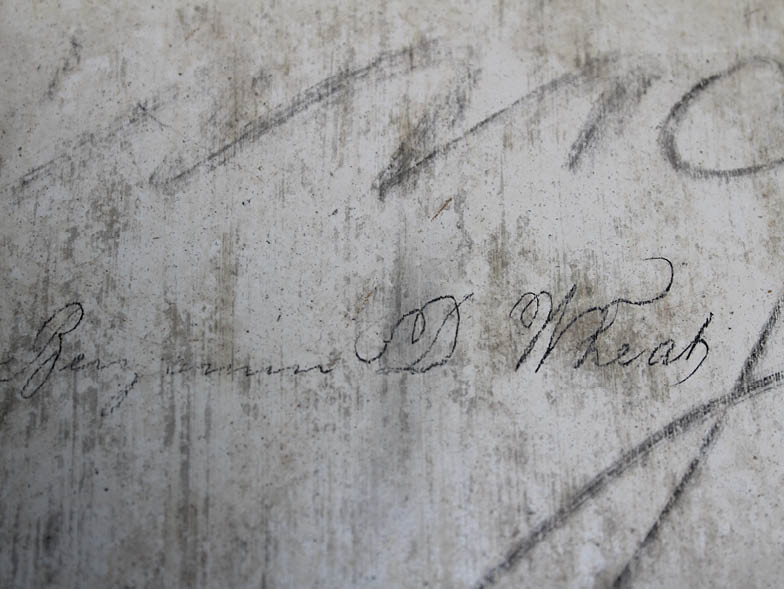

An item sold at Blenheim’s 1997 estate sale first offered a hint that the home’s graffiti might not be contained to the attic. A board member of the nonprofit Historic Fairfax City, Inc. purchased a datebook that belonged to the Scotts, which mentioned a November 1964 discovery of a drawing on a second-floor wall. “That made us think, why wouldn’t there be graffiti in other places?” Loewenwarter says.

Conservator Kirsten Travers Moffitt was hired in 2006 to uncover more of Blenheim’s story. Her goal was to strip the walls without damaging the possible graffiti underneath. “I was sitting there, wearing a respirator because of paint stripper, with my face three inches from the wall,” she says. “I started gently scraping away the softened paint, and I saw a foot. So then I kept going, and I saw a leg. I started realizing that I was uncovering something that no one had seen in at least one hundred years.” The painstaking effort had a positive result: graffiti was indeed on all the walls.

This discovery would not have been possible if not for Carney and her neighbors’ fight to save Blenheim a decade earlier. The five knew they only had months, not years, to produce research notes, talking points, and executive summaries. They took on an official title, the Citizen Coalition for the Preservation of Blenheim. One belief bonded them: this place and this history could not be destroyed. “Once it’s gone, that’s it. It’s gone. You can’t bring it back,” says Preiss.

Expressing that urgency to approximately 21,000 city residents was a challenge. This was before social media—and its potential to reach thousands of people—existed. Their only option was one door and one phone call at a time. Family members of the five were not exempt from this all-hands effort. Loewenwarter’s husband, Jim Gillespie, pushed their son in a stroller while canvasing neighborhoods across the city. Their two-man mission was to distribute flyers titled “Protect the Past for Your Future.”

Preiss became the “town crier” of the coalition outside a grocery store. “I literally stood on a box with a picture of the house that said, ‘Save Blenheim,’” he recalls. “People would stop and say, ‘What’s this?’ and I would explain it over and over until my voice gave out. I did this eight to ten hours every Saturday for weeks on end.” More neighbors joined their volunteer effort. They were making an impact.

But others, who saw Blenheim as no more than an old house on prime real estate, were moving at a quicker pace. “Once the developers began to display their proposals in city hall, people told us that it was all over and that we should give up,” said Preiss. A bed and breakfast, a community center, and a townhome development were among the plans.

On June 2, 1998, the attorney handling the Scotts’ estate informed the coalition that written offers for millions of dollars were being accepted for the property. The group of neighbors did the only thing they could: they contacted national and local historic preservation organizations and hoped for a buyer. No sale was made. It seemed likely that Blenheim would be lost to development.

But the coalition had one more card to play, a “protective bubble” tool that it urged the city to adopt. Three weeks later, the City of Fairfax held a joint city council and planning commission public hearing. Under consideration was the creation of the Blenheim Historic Overlay. It would make the property unattractive to developers through burdensome preservation regulations. It passed. Yet Blenheim was still without a buyer.

The property was one of the last parcels of land for sale in the city. What began as an effort to save local history grew into a campaign to protect something the city realized it also valued: open space.

In January of 1999, the city council voted to purchase Blenheim and its twelve acres from the Scotts’ estate for $2.275 million. The first annual public tour of the house and attic began the same year. Eventually, it was determined that the house was not stable enough to support visitors on the upper floors. A solution was needed. How could an attic be moved to another building? The answer was to copy it. And that’s just what they did.

The Civil War Interpretive Center at Historic Blenheim opened in November of 2008. The 3,800-square-foot facility, a $1.5 million city-funded project, is part of the historic home’s twelve acres. The center presents the Civil War in the context of its impact in Virginia, the Willcoxons’ family history, and a full-scale replica of part of the attic graffiti.

Twenty years after the coalition’s goal was achieved, Blenheim’s history remains enduring. The Blenheim house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2001. Approximately 1,500 people attended the 2018 Fairfax History Day held at the property. Those who had never seen the home were awestruck, even if they could only tour the first floor.

The five were named Citizens of the Year in 1999 for their efforts to save Blenheim. Yet, to them, the accolades never mattered. What they valued most was changing the fabric of their community for future generations. Decades later, the groundbreaking for the Interpretive Center remains an emotional moment for Carney. Welling up, she recalls, “I looked at David and said, ‘We did it.’”

For more info, visit fairfaxva.gov/government/historic-resources/historic-blenheim