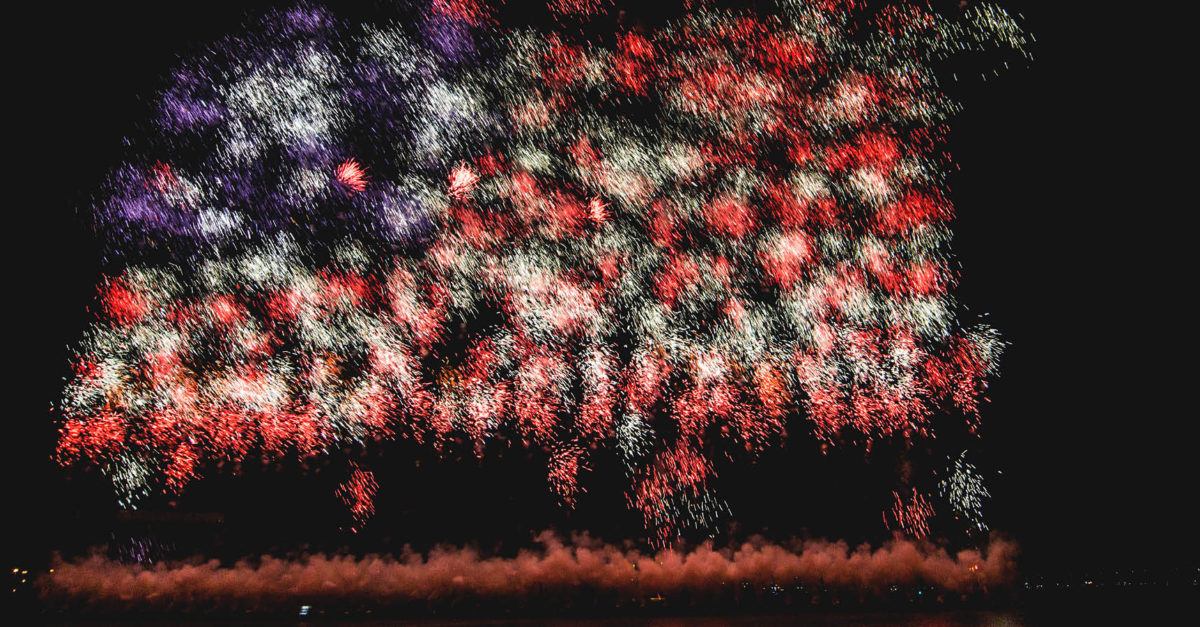

A Fireworks Family Affair

An unlikely talent sprouted from the small town of Bari on Italy’s Adriatic coast in the 1800s. In a country known for its cuisine, fashion, and architecture, one man found his calling as a pyrotechnician—helping to bring the art of firework making into the public eye.

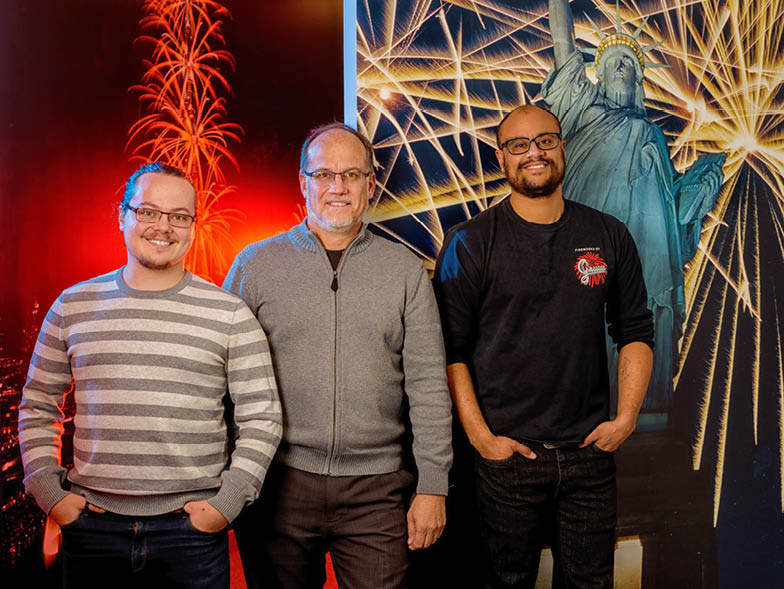

What started out as a hobby quickly became the family business, and now, having crossed continents and spanned over more than five generations, the Gruccis—America’s first family of fireworks—continue to astound as true pioneers of the craft.

Who was Angelo Lanzetta, and how did he develop an interest in pyrotechnics?

Angelo was my great-great-grandfather, who started our business in Bari, Italy, in 1850. He had a hobby of making fireworks, but back then they didn’t have the large shows that we have today. Firework making was more of a trade where people would produce individual fireworks and compete with other local artisans on the elaboration of that product.

When did he decide to turn this hobby of firework making into a business?

Angelo decided to leave Italy in 1870 with his son, Anthony. They came to New York through Ellis Island and set up shop in what was practically nothing more than a cardboard box, right outside the island. They produced and sold fireworks in the same location until Anthony’s nephew, Felix Grucci Sr., bought the business in 1923.

How did Felix Sr. help catapult the business to the level that it has grown to today? What were some of his important innovations?

As the company has progressed, each generation has left its own mark and attributions. One of the most important elements that Felix Sr. left the company is our contract with the military, which came about during the Korean War in the 1950s. This contract helped us establish a larger factory to work with and therefore transition into the production of larger pyrotechnics.

During these years, Felix Sr. also developed one of the most important improvements in the history of the industry—the stringless shell—which helped to make fireworks displays much safer. One of the biggest safety hazards with these displays was the fallout from the explosions, which could land on cars and homes from miles away. Now, when fireworks burst in the sky, there is much less fallout.

Was there a particular performance that helped make Fireworks by Grucci the number one player in the industry?

Our first big show outside of the New Jersey-New York area was over the Charles River in Boston, during America’s bicentennial. Then, in 1979, we entered into the Monte Carlo International Fireworks Festival, where we became the first American family to win the gold medal—breaking the world record for the largest firework in the process. This was a huge achievement for us, because this is really the most prestigious fireworks competition in the entire world.

Can you explain some of the techniques that your family has pioneered in terms of fireworks technology?

Our medium is very exciting because it’s constantly changing. We provide fireworks products to some of the biggest events and companies in the world, such as presidential inaugurations and Disney, for example.

One of the specialty products you will see at these shows is the golden center split comet, which we developed the shell for in the 1970s. We typically use it as a prelude right before the grand finale because it has a tapering, streaky effect that, just when you think is over, splits apart elegantly.

We also created the pixel burst, which is a small microchip embedded in the shell that allows us to control the height and timing of the burst. We make these exclusively at our factories in Virginia and New York.

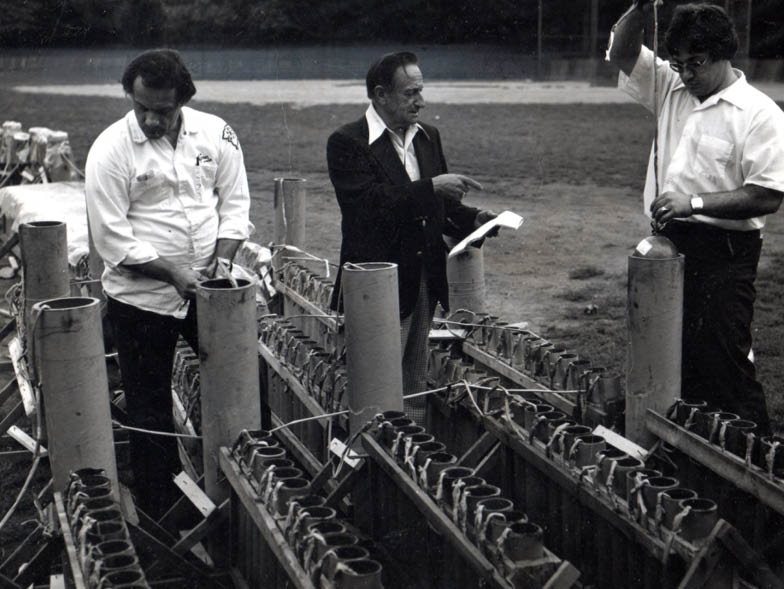

What is the process for putting on a fireworks show, from start to finish?

All parts of our performances are very design driven. Fireworks are our artistic medium, just like paint, pencil, or chalk. First, we look at the structure of the stage, bridge, field, or whatever area we are working with, and then we figure out how to marry the location with the theme of the performance, including music.

After that, the engineering takes place over a few months. We never want to repeat a design in a show, so it’s a challenge to make it all happen and keep the audience from guessing what they’ll see next. We also have to consider the shipping, storage, and logistics; for example, at one of our performances we served 1,500 meals just to feed the crew who would be setting off the fireworks.

You also hold training seminars for the education and safety of the people lighting the fireworks. What do these courses entail?

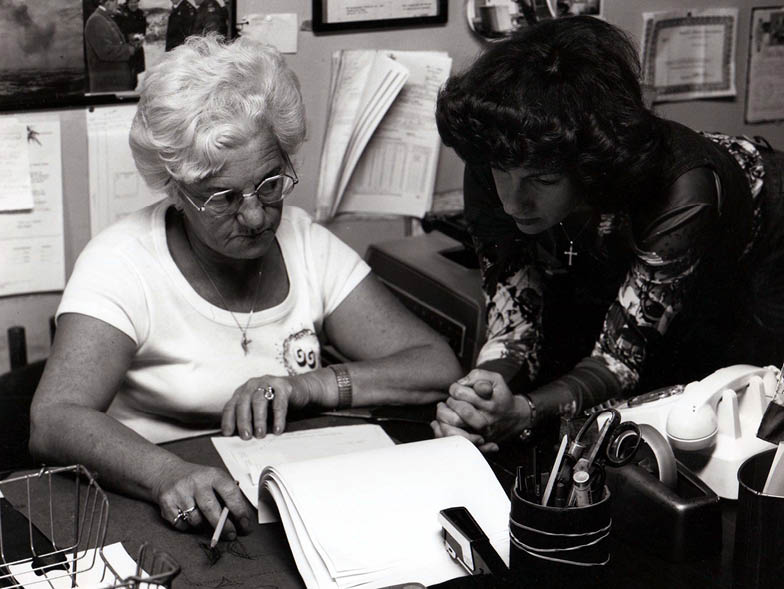

The most important part of our business is the people. Because we are working with hazardous materials, training is critical for us to sustain the business. We generally hold training seminars in the spring, and they are made up of a mixture of pyrotechnicians and those interested in joining our team through this program.

The course is four days long, and it goes through every aspect of our business, including federal regulations and state-by-state regulations. When students come out of the course, they typically go out to their first show with the assistance of a chief pyrotechnician and practice their skills in the field. The 2017 class graduated sixty pyrotechnicians, who were scheduled to practice work in the field before the Fourth of July.

What has been most rewarding for you in taking over the business that has been in your family for so many years?

The training and sense of pride in this business through each generation have allowed us to keep the business together. I am proud to say that, even though we lost my father—who was really the life of the business—in 1983, we pushed through and were able to build it back up.

I am very fortunate to see how the industry has changed—with electronics in the early 1980s and computers in the 1990s, all the way to the elaborate technological achievements we see today.

For more info, visit www.grucci.com