Amber Cowan’s Generations of Glass

Antique gravy boats, candy dishes, vases—they all have a story to tell. Objects like these are passed along from generation to generation, and, though their origins might be a distant, foggy memory, the importance of these items in the timelines of families is unquestioned. Some will eventually end up in antique shops and flea markets, to be found by collectors—knowing that these items were once a part of someone’s life. Perhaps they followed them from their childhood home to their first home, to their children’s first home, and beyond.

Amber Cowan has always been fascinated by the nostalgia and splendor of glassmaking. She fondly remembers gifting glass to her mother on special occasions. Her love for the intricacy of the craft and passion behind the art started young, and, though she didn’t know it at the time, this affection would eventually transform into a career.

After graduating with a degree in 3-D design from Salisbury University in Maryland, Cowan began work with a number of mentors in New York City, who helped her develop her own style and methods and who would shape her business practices as an artist. “I worked for a woman named Michiko Sakano—helping her in the studio, charging the furnace and assisting her in the hot shop,” she explains. “She’s really one of the glass bosses of New York, and she taught me not only a lot about technique but also about being a professional artist.”

In her fifteen years as a glass artist, Cowan has studied at a number of schools across the country, including the famous Corning Museum of Glass and Pilchuck Glass School, and, most recently, has taught at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University, where she also received her master’s in glass and ceramics. She has learned from a crop of the best glass artists in the world, and she also has taught the upcoming class of artisans who will continue to evolve the art form. One of the most important aspects of glass artistry has always been education. Because glass production in America began in the factories before transitioning to the artist’s studio—and because it’s a relatively new art form in this country—instruction and experimentation are key.

Cowan’s technique is a combination of the ancient style of soft Venetian glass sculpting, mixed with flameworking practices she has picked up from mentors and those she developed herself. “I’ve always been attracted to work that has a lot of detail, as well as pieces that you can get lost in and see different things in all the time,” Cowan says. “I think that comes from books, art, and other things that have influenced me throughout my life—the ones that leave me constantly searching.”

Her most recent works are awesome, large-scale pieces full of intricate detail, and, true to form, include found objects that she has hunted for herself or were sent to her by other people intrigued by her art. And, though Cowan has always had a personal interest in found glass, it wasn’t something she used in her work until an experience in the studio at Tyler.

Behind the large furnaces, she discovered a barrel of broken-up, light-pink-colored glass that no other students were using. She decided to melt the glass down and attempt to work with it the same way she had been with other glass. Much to her surprise, the glass fired the same way. “I discovered later that the barrel was from an old pressed glass factory in West Virginia that produced tableware,” she reveals. “When I dumped it out, I noticed that the pieces were actually from twentieth-century Easter candy dishes.” After doing some research, Cowan found that the type of glass she discovered, called cullet, was the same as that used by early studio artists during the 1960s—when production first began moving out of the factories.

She has continued to use found glass in her work ever since and divulges that the process of collecting these items and receiving them from others has turned into one of the most exciting parts of her career. “A woman in Michigan once sent me a package that contained two antique pieces from the 1800s,” Cowan says. “Her great-grandfather had won them at a state fair, and he gave one of the items to her great-grandmother as an engagement present. A lot of times, the people who send me glass feel bad throwing it away even though it may be broken. Sometimes they just don’t want it anymore, but it’s a family heirloom or it has some sort of sentimental value, so they send it to me so that it may continue living through my work.”

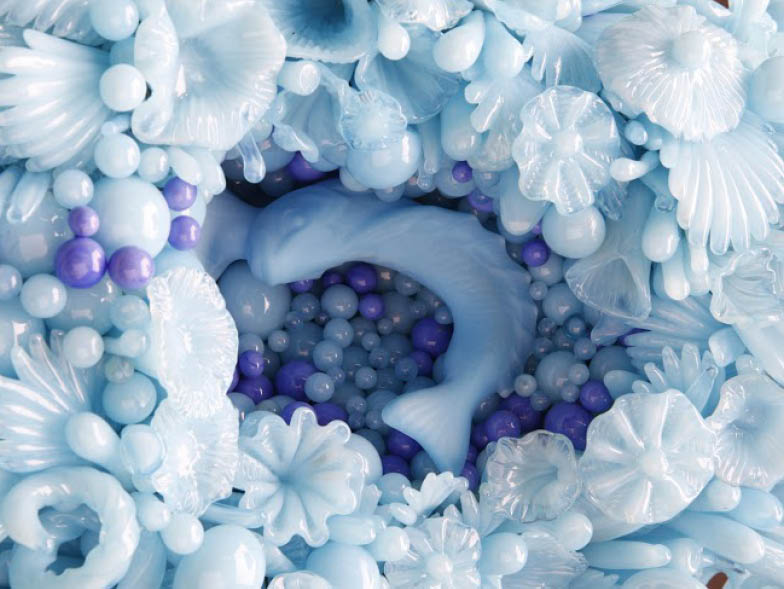

One of Cowan’s favorite pieces, Creamer and Sugar, Swans in Sky—debuted in 2016 at the Heller Gallery during Art Miami but moved to an exhibition titled Amber Cowan: Re/Collection at the Fuller Craft Museum in Massachusetts in June 2017. The piece features a number of found glass animals and objects that add depth and history to it. In a sea of blue, viewers can spend hours finding new elements in the piece, like an antique swan creamer set, buried in a sea of bubbles, shells, and swirls.

Although glassmaking is a uniquely personal experience for each artist, it is also a difficult craft to master without the inspiration and assistance of other artisans. Cowan reiterates, “It’s hard to be a glassmaker on your own, so the glass community is very connected,” she says. “I work on a block in Philadelphia that has twenty-two other flameworkers. They all make very different work, but it’s great to be around that energy where people are working hard and creating all of the time.”

This synergy and emotional connection is what continues to drive Cowan’s work. Cowan says she has yet to come across a medium that is as conducive to her vision quite like glass. As she digs into the history of American pressed glass with each new project, experimenting with repurposed materials and telling the stories of the people who once treasured these objects, she taps into an era of American craftsmanship once forgotten, but now preserved, eternally.

For more info, visit www.hellergallery.com/amber-cowan or www.ambercowan.com