The Language of Art

Colombian-born Patricia Riascos took full advantage of her second chance at the American Dream, carving out a career in the medical field before pursuing her true passion: art, through which she creates a canvas-centric dialogue with her audience.

Tell us about your upbringing in Colombia. Were you raised in an artistic household?

I grew up in a relatively small town right in the middle of the coffee region in Colombia surrounded by amazing landscapes and the most beautiful greenery—something that you truly appreciate once you have left it behind.

I do come from a family with an artistic soul. My mother never had art instruction, yet she painted watercolors and was a great gardener and flower designer. Her side of the family shows artistic traits manifested in many different ways, as several relatives are published writers. My brother is an architect and also enjoys painting. My two sisters both have artistic talents.

When did you move to the United States?

I had a great experience as an exchange student in Illinois, and then I returned to Colombia to attend college. After finishing school, I received a Fulbright Scholarship. Due to paperwork confusion and lack of advice, I had to let it go at the last minute. That is something that has always haunted me—a great and unfortunate loss. I decided that I would come to the States anyway. I saved a little money and moved to California on my own in 1984.

How have your travels influenced your artwork?

My art is, for the most part, emotional. When I travel or go back to Colombia, the feelings that I gather inspire me. As many people know, Colombia

has suffered more than forty years of terrorism, but people like me, who are part of the diaspora, have not lived those difficult times.

Several years ago, I spent a good amount of time reading and learning about this suffering, which inspired me to create a small series representing my sorrow as I learned the facts. I have not shown most of those paintings.

You had a career as a lab medical technologist but quit to become an artist. What prompted you to do so?

Older generations tended to advocate security instead of passion to their children, so it was decided that I should be in a field that would provide more of a secure future, which I agreed to (and I feel that this decision served its purpose). But I also pursued art on the side, going to art schools more as a hobby. The change to art happened slowly, coinciding with fewer hours at the laboratory.

I feel great satisfaction being able to dedicate more time to something that makes the hours go by without me noticing and resolves the urge to create. The results are a source of happiness for me beyond any limits.

On your website, you have photos of your studio. It’s very neat and organized—except in the photo of you painting. Do you work better in chaos?

My studio is neat before I start a new project. As I paint, though, a hurricane of debris starts to populate the surfaces. Since I often work with collage, all kinds of boxes, each containing different materials, are open and books are consulted. I don’t want to spend the time on getting things organized as I go; I feel the urge to concentrate on painting. Then, after I’m finished, I need to have my studio completely clean and back in order before I start anything new.

Your recent paintings are more abstract, but you’ve also done representational art. Why did you switch?

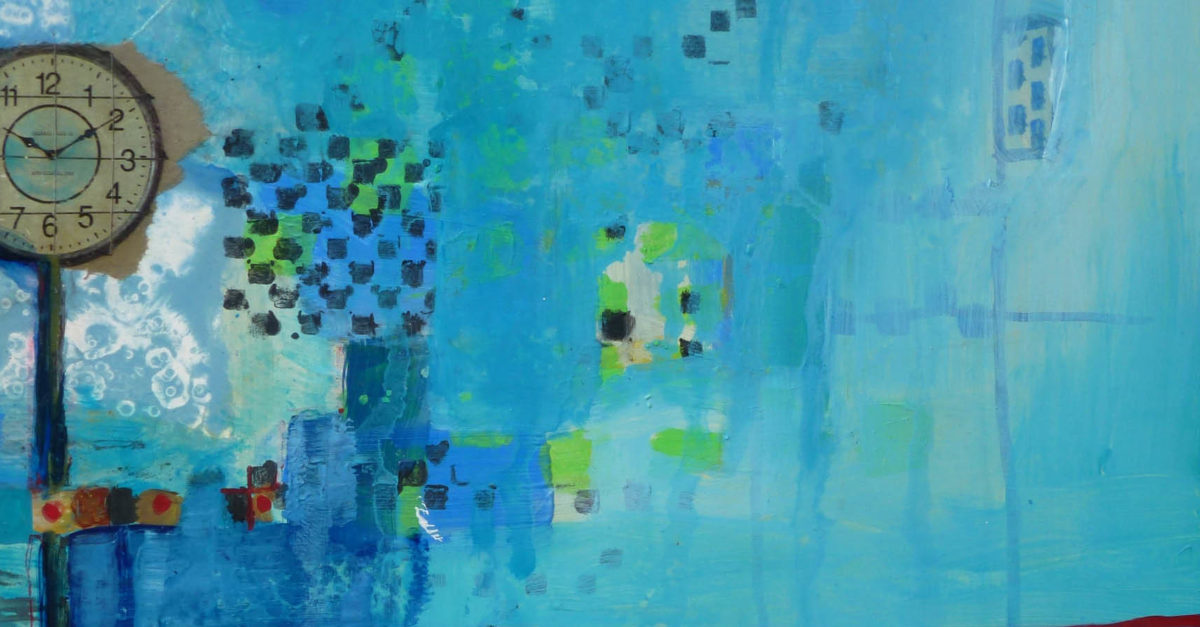

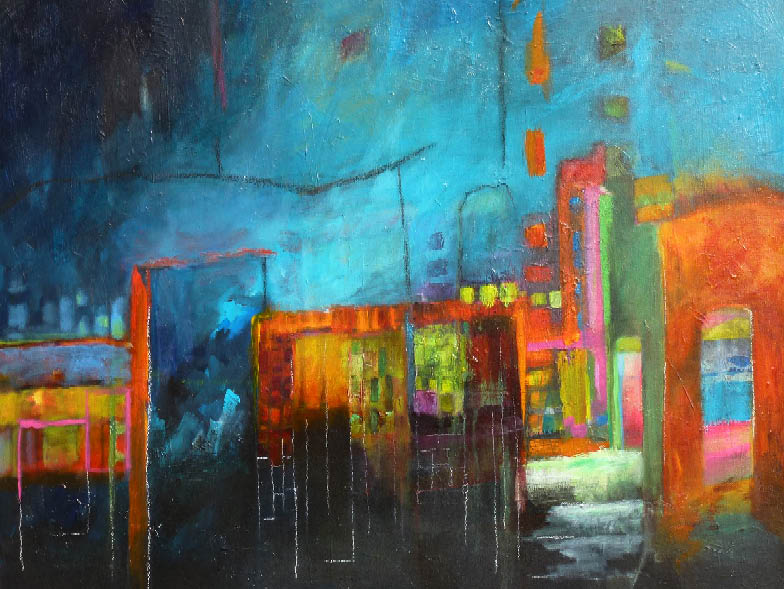

I have worked in the representational style but never too close to a complete copy of the subject. I have always admired abstract art but never actually had classes. I felt a great deal of curiosity about learning and decided that I would immerse myself in it. In my opinion, abstract art is a bit more difficult; there is nothing to copy from, and everything has to flow from your own intentions. It also demands a more disciplined sense of design, contrary to what people believe. At the moment, I am mixing both elements.

Your overall style is very free flowing, yet you also make ample use of squares, which are very structured shapes. What does this combination add to your artwork?

You touch on a very good point. I have actually thought about this concept. There is the idea of a “square person,” who is supposed to be unwilling to accept other beliefs or external influences. However, I find that squares are very versatile in a painting: they add variation, texture, and fun, especially when mixed with a free-flowing style.

Lines are also prominent in your artwork. What do they bring to your art?

For me, lines are a very adaptable element. I enjoy using them; they can be very expressive, strong, or delicate. Picasso is my favorite artist. I have studied and admired how he could depict almost an entire painting with a few strokes. I use lines at all stages, sometimes as the final touches on wide spaces.

How do your paintings express what you’re feeling?

I believe art is a language, much like music and the written word. If you don’t speak the language, it is hard to understand it. That’s why I think it is important to include art in the school curriculum.

There are certain elements in art that communicate feelings. It is up to the observer to establish a connection. Sometimes a person is drawn to a particular painting because it awakens memories or emotions that don’t necessarily coincide with the artist’s intentions but still produce a successful interaction. I like it when someone tells me about their own interpretation, which might be totally different from my intentions. It is also rewarding when someone gets exactly what I intended. It is an open dialogue.

You also occasionally include messages in your paintings. What determines if you do?

I enjoy writing. My mind is constantly at work as I go about my day. I collect all those thoughts in a little notebook. Sometimes, when I am deciding on my next project, I refer back to my notes. Then a painting is born and those words go on it, or it will be the title of the next painting.

One of my favorite examples occurred after I was moving from a house that I had lived in for twenty-one years. During the time I spent packing, I started to think about how fortunate I was to have so much to pack and how the process was almost like reviewing your life and remembering the nice things that people have given to you. As a result, “Nothing like packing to move to see your life in front of your eyes” is written in one of my paintings.

What is more rewarding: a painting that comes to you easily or one that you have to put a lot of work into?

The fact that I could come up with what could be considered a successful painting is rewarding no matter what. If the painting went through a long process, it is like a child that demanded a lot of time and patience.

Paintings are very much like children to me; it is very hard to let go of them. Once, I sold a very dear painting to an institution. On one occasion, I went to see how it looked. When I saw it, I wanted to cry. It was hanging in a long, somewhat dark corridor, on a wall too big for its size. I felt that it was very lonely. I wanted to buy it back!

If you could go back ten, twenty, or thirty years, what advice would you give to yourself?

Work harder, invest more time when possible, and think well before you go into endeavors that look like great opportunities. Do better research and, more important, a better soul search.

For more info, visit patriciariascosart.com.