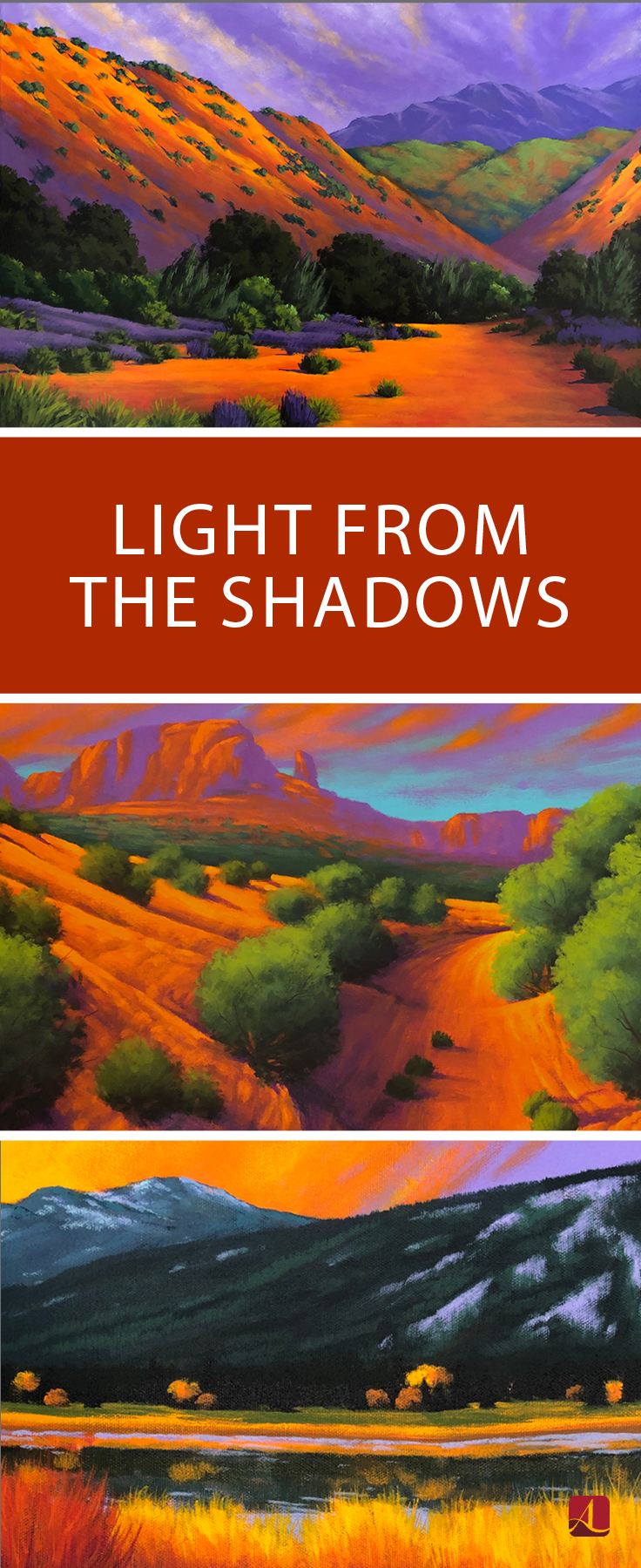

Light From The Shadows

PAINTER JOE A. OAKES DISCUSSES HIS LONG PATH TO BECOMING AN ARTIST AND HIS WORK’S FOCUS ON COLOR AND NATURE.

Has art always been part of your life?

My parents encouraged my artmaking, and I was even tagged as “the artist” of the family. Back then, art was encouraged in school, so that was a way for me to excel. I received a lot of positive feedback from my teachers, which always stuck with me. It hasn’t always been easy, of course. I wasn’t the greatest student in high school. And it wasn’t until I got married and moved to California in the early nineties that I went to college. At the time, my wife said, “You can’t just get a degree in painting” (which secretly was my plan), so I got my bachelor’s degree from Cal State Fullerton with a concentration in graphic design and then went into design. In fact, I didn’t even take a painting class in college.

You’ve also dealt with personal tragedies: cancer and the loss of a child. Would you elaborate on how they affected you?

When you go through something like cancer, you always say that you’re going to be a better person and do things you want to do. And that’s what I thought. But then you get right back into life and lose a little bit of that motivation. In contrast, when my son passed away, I was so numb. Your thinking is so different, and you don’t really consider what-ifs. I don’t think my wife would have ever let me go down this art path if it wasn’t for that situation.

What helped you grow as an artist?

I’ve learned a lot. In the beginning, I had a good grasp of composition, color, and balance from college, but I took the process of painting for granted and struggled with it. Thankfully, I started doing workshops. There my failure was invaluable because I could look at somebody’s work and say, “I know exactly where you’re at, and I’m going to tell you what you need to do to get better.” That helped me improve my work because it made me think about my process.

You didn’t paint at all in college, so how did you become an acrylic painter?

I want to approach things in the simplest, most straightforward way I can. I started with pastels, figuring it would be an easier transition from drawing because they’re like pencils. Well, that wasn’t true. I enjoyed pastels, but I had a hard time because you’re not mixing color; you’re layering it, which I couldn’t make happen. Plus, pastels are messy, and I don’t like to clean anything. Don’t get me wrong—I love oil paint, even the smell of it. But we only had acrylics in high school and they’re easy to use, so that seemed like a natural place to start.

How has California inspired you?

I have a good story about this. In Chicago, where I grew up, it’s almost all flatland. Still, when I was ten years old, I did a painting of mountains and a lake. After we moved to California, we eventually settled in Orange County, which has a man-made lake with mountains as a backdrop—the exact scene that I painted as a child. Somehow, I was inspired by these mountains and lakes and trees that I knew existed but had never seen. I feel like I was meant to be here.

Is there an artistic mantra you live by?

Perfection is the killer of creativity. When you focus on being perfect, it takes all the life out of art. So I try to avoid that and take a lot of artistic license.

What inspired you to try architectural paintings?

When I was a kid, old buildings fascinated me. At some point, I thought I wanted to be an architect. So coming out here and seeing a whole different style of architecture, especially Spanish style, inspired me. I haven’t been as successful with it because I worked on my landscapes so much. If you’re going to survive in this business, you must master a primary style.

Your work features dichotomies like sunrises and sunsets, and shadow and light. Is that something you focus on?

Photographers wait for the perfect light and the perfect shot, but artists must be able to look at things as they could be. In art education, you’re taught that if you want to make things lighter, like a highlight, you add white to it, and if you want to make things darker, like a shadow, you add black to it. But most people add too much white or dark, so the color’s essence is lost. After working on this a lot, I decided to just use colors I like to make shadows and figure out which objects and shapes they lend themselves to before I start blocking. It was like a light bulb went on for me, and people responded to it. I’m not sure how I did it, but for paintings that are so vibrant, people always tell me they’re both happy and calming. I also don’t want to include anything that indicates they’re looking at a real scene, so I minimize distractions like objects and animals in my paintings. I want them to feel like they could walk into it. To me, a painting, no matter what size, is like a window—there’s a whole other part of the world outside the frame.

What messages do you try to convey about nature?

We take it for granted. I could have twelve people in my workshop, and I guarantee you 90 percent of them would say the sky is blue and the grass is green. That’s what you see, but most people don’t really look at the colors because they’re busy, don’t think about them, or don’t appreciate them. Our brains are like supercomputers, always trying to find the quickest answer. So I want to get people to think about nature more deeply, especially its colors. I want to help create conversations, internally and externally, about nature through art. Nature is amazing; we can’t even completely grasp it.

How has outside-the-box thinking served you well?

If you want to be successful at anything, you should think a little differently about it to create some interest, reveal who you are, and explain where you’re coming from. As artists, we can take something that may seem mundane, that people drive by a million times and never think twice about, and make it interesting and unique. I think true artists understand this, and that’s what they’re always working toward.

For more info, visit joeaoakes.com