A Top-Shelf Community Institution

A library is not a luxury but one of the necessities of life.

—Henry Ward Beecher

A common misperception in the internet age is that libraries are a thing of the past. In reality, they are arguably more important than ever. According to the American Library Association, there are over 17,000 public libraries alone in the US—that’s more public libraries than Starbucks locations. On average, over four million people walk through their doors every day.

One of the institutions leading the way is the Kansas City Public Library—which has been a trailblazer in Missouri since opening in 1873 with a single set of encyclopedias. Over 140 years later, the library has 250 people on staff (including part-time and substitute workers), who welcome over two million physical visitors a year to its ten locations and two million more through its digital branch. It also has over two million materials, including books, of course, but also e-books, audiobooks, DVDs, and CDs.

Just as important as these impressive numbers is another number: one. The library’s mission is to be the singular place in the Kansas City community where everybody can gather to learn, to grow, and to have a dialogue.

“Perhaps no place in any community is so totally democratic as the town library. The only entrance requirement is interest.” —Lady Bird Johnson

According to executive director R. Crosby Kemper III, the library has been returning to its roots and fulfilling its original purpose to the city. “Kansas City was very focused on intercultural and immigrant populations and had a very racially diverse population in the very beginning in the 1820s,” he notes. “But by the end of the nineteenth century, it became substantially white. That’s been changing over the past twenty to twenty-five years. Black people and white people now each make up a little over 40 percent of our population. The immigrant population is a fast-growing population in Kansas City. We have materials in the library in about twenty languages that are regularly used.

“Historically, this library was always a place of self-education and drew people from all over the community,” he continues. “By the time we had an independent building starting in 1889, we also conducted dialogues around great ideas and civic issues. So there was a tradition in the Kansas City Public Library of playing a civic role and bringing people together around that role.” In the past few decades, the library has revived this role, becoming the epicenter for many of the area’s public meetings about politics, social issues, and more.

The library had long been part of the school district—its original name was the Public School Library of Kansas City. It rapidly grew in popularity from the outset, so much so that over 20,000 people visited within the first two days after its new location opened in 1897. A year later, in a nod to its civic role in the community, the library became free to the public. It split from the school district in 1988 and built a series of freestanding libraries in the 1990s.

But perhaps Kansas City Public Library’s most ambitious initiatives to date have happened in the twenty-first century. In 2004, right after Kemper joined, the library’s Central branch moved into the hundred-year-old First National Bank building. Of course, converting a bank with marble columns and bronze doors into a library has its advantages, one of which is the Durwood Film Vault—the bank’s former vault—where the library now holds movie screenings, private parties, and more. Other amenities include meeting spaces, an auditorium, a coffee shop, and a rooftop terrace (which also hosts movie nights). It has even hosted weddings. “It’s turned out to be a really wonderful reuse of a great building,” Kemper says of the award-winning enterprise.

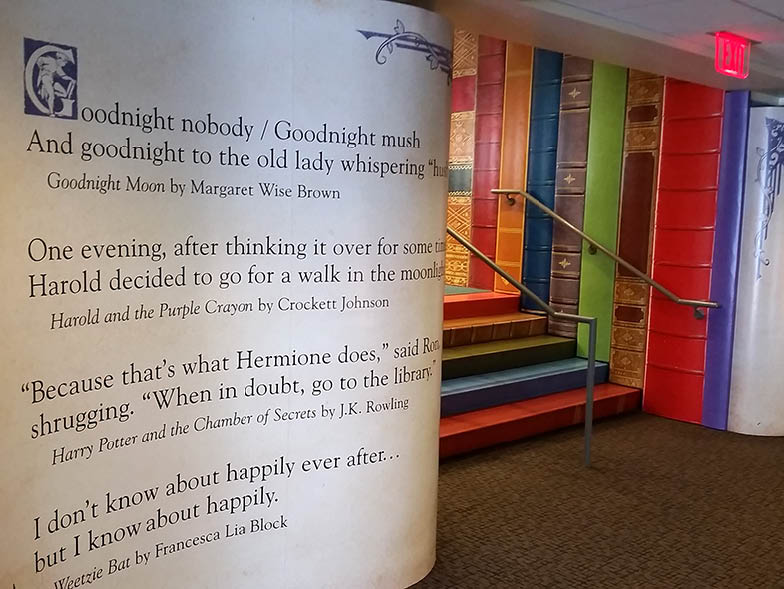

Another reason for the library’s popularity is actually outside the Central library. Its parking garage features a magnificent, colorful series of twenty-five-foot-high book spines aligned in what’s called the Community Bookshelf. This piece of art has gone viral, landing on several “must-see” lists for buildings and architecture, helping the library to attract visitors from all over the world, despite being located in a smaller United States city.

“A library is a place that is a repository of information and gives every citizen equal access to it. That includes health information and mental health information. It’s a community space. It’s a place of safety, a haven from the world.” —Neil Gaiman

Within its community, the Kansas City Public Library has also been a groundbreaker with the programs it provides, offering a seemingly endless amount of benefits. Every year, for example, over 130,000 people attend adult events, such as readings, and 80,000 kids attend children’s events like story time and Friday Night Family Fun. Teens can get homework help, enjoy gaming, or use the digital media lab to learn things like robotics and media production.

“We’ve built world-class public programming and have really become the intellectual center of the city,” Kemper states. “We do more public programming than anybody else. That’s been important to me.” One key initiative involves health care. Community members can participate in weight loss programs, take exercise classes, have their blood pressure checked, and even get help with things like eye care. Also at the forefront is job skill development. The library offers digital certifications; consultations with librarians for developing job skills and starting small businesses; and help with job searches, résumés, and online interviews. “Everything in the job universe is now virtual, and libraries are the place where folks on the other side of the digital divide, income divide, or racial divide come to get help,” says Kemper. “I think we’ve been a leader in that.”

An excellent example of this, according to Kemper, is the library’s Career Online High School. “In this digital space, we’re actually graduating kids from an accredited high school. It’s a big step beyond the GED we’ve always done,” he says. “We also have something called P2PU, or peer-to-peer university, which is developed out of the MIT media lab. It’s, in essence, a do-it-yourself online postsecondary education. All of this is very career-oriented toward developing accredited skills and is directly related to needs in the community. It shows that the library can be a place where people can come to develop these skills. What used to be completely inside the formal education universe is now available in the library in virtual ways and, in some cases, real physical ways. That’s important.”

“When I read about the way in which library funds are being cut and cut, I can only think that American society has found one more way to destroy itself.” —Isaac Asimov

Of course, opening the doors to so many possibilities for so many people in the community costs money, and getting sufficient funds without burdening the population it serves is something that the library has fiercely fought for since Kemper took the reins over a decade ago.

“When I showed up, I was given a budget that was very complicated. It looked like we had a big deficit, which was one of the reasons they hired me, but we didn’t,” he reveals. “We had a large budget because of money donated by the Kauffman Foundation, a nonprofit that supports education and entrepreneurship in Kansas City. Out of that, we built that world-class public programming, which is probably the best in the country, in my view.

“But our biggest challenge is still financial,” he explains. “Functionally, we’re 90 percent property-tax funded; however, we’ve been working on diminishing that through private fund-raising. It’s hard for a library to do on a consistent basis, though. That creates a financial challenge as we try to find means to provide services while also maintaining our branch system, which is now about twenty-five years old and is showing the kind of wear you’d expect.”

With added revenue, the library would aim to partner with other organizations to get its services even closer to the community. “We know that we serve probably 60 percent of the population on an annual basis in one way or another. Another 20 to 25 percent of the population needs us, but we don’t get to them,” Kemper says. “One of our goals if we get new money is making sure we get to everybody who needs us.”

“I always felt, if I can get to a library, I’ll be OK.” —Maya Angelou

In many respects, the Kansas City Public Library has come full circle in its mission to be a community haven—and then expanded it. Combining the welcoming, open environment of its past with modern twenty-first century technology, it serves as a shining example of the important role libraries play in America today.

For more info, visit kclibrary.org