Painting a Navajo Narrative

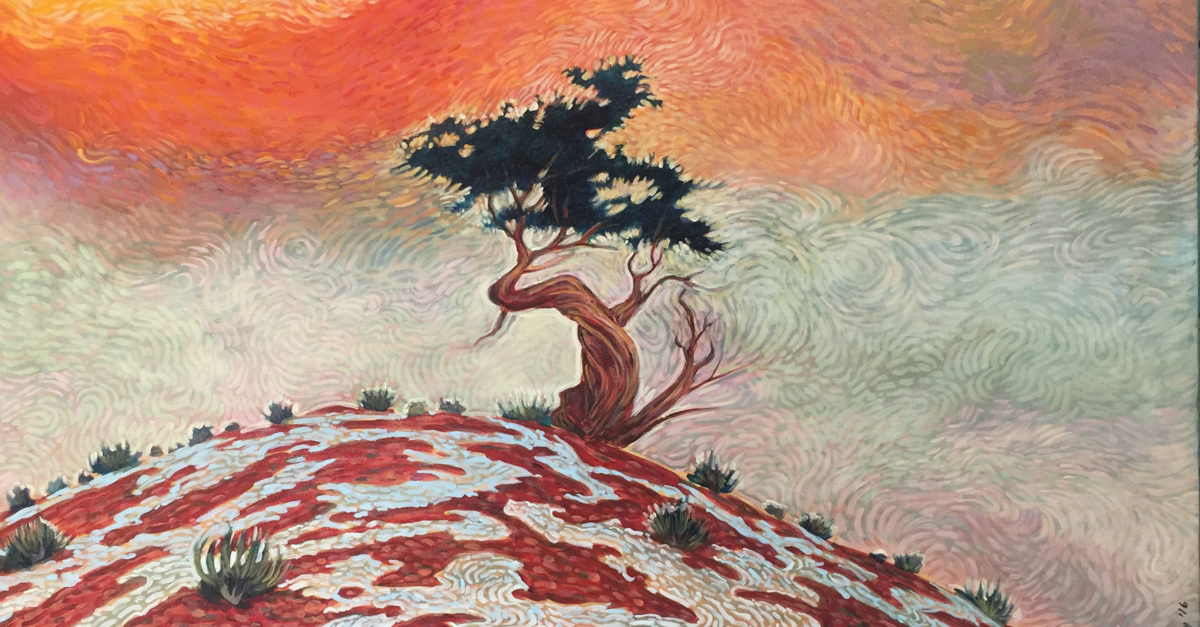

Multitalented painter Shonto Begay discusses what influences his art’s subject matter and style, including his culture, his days as a shepherd, his dreams, and comic books.

What was your family life like?

I had a very traditional Navajo upbringing and was one of sixteen kids in my family. We lived in a hogan (a small earthen dwelling) in Arizona, with no television, no electricity, and no running water. My father was a revered Navajo medicine man, and my mother wove the famous Navajo rugs. My sisters, aunt, and grandmother all wove, too.

Did you work a lot? Play a lot?

It was a very communal living situation. My older brothers, sisters, cousins, and I tended to the sheep, goats, donkeys, horses, cattle, and chickens. Our farm and its huge cornfields were a communal responsibility as well.

Everybody knew where they were needed the most. My older brothers and cousins were strong, tall, and fast, so they did more adventurous things like hunting and chasing wild horses. I was the smallest, so I was relegated to tending to the sheep and goats at a very young age. My sheepdog and I were out there all day long, so my mind opened up to imagination—being alone in the elements gave me a lot of time to think, reflect on my world, and be intimate with my environment. Listening to the silence, smelling rain two days away, and knowing what was going to happen with the wind taught me a great deal. There was a lot of time for playing with my siblings as well since we didn’t have things like modern toys.

How did your upbringing lead you to art?

There was a lot of vivid storytelling around the campfire, and my culture also respects images: every line and drawing that you make and every interpretation you create is a form of scripting to the spirit world. I was definitely influenced by this.

I started drawing at around age nine. I would use anything that came within my reach—an old can, cardboard, or things that were blowing across the valley—and drew on it with anything that could make a mark, such as charcoal or a piece of rock. It wasn’t until my twenties that I realized that I could go to school, get an art degree, and make a living with art.

You have a mantra that “art saves lives.” Would you mind elaborating?

As kids, we were forced into boarding schools by the government; it was there that I started using art materials like crayons and drawing paper, and I started interpreting my world and documenting my life. Bullies were all around me in those schools, but drawing protected me a lot because they liked my art.

I would also draw to escape into my own unconventional reality somewhere else—art kept bringing goodness, beauty, and strength to me, and it kept my spirit and voice alive in those very harsh conditions.

So, yes, art saves lives. I am a living, breathing testimonial to that.

Are your subject matters fictional or nonfictional?

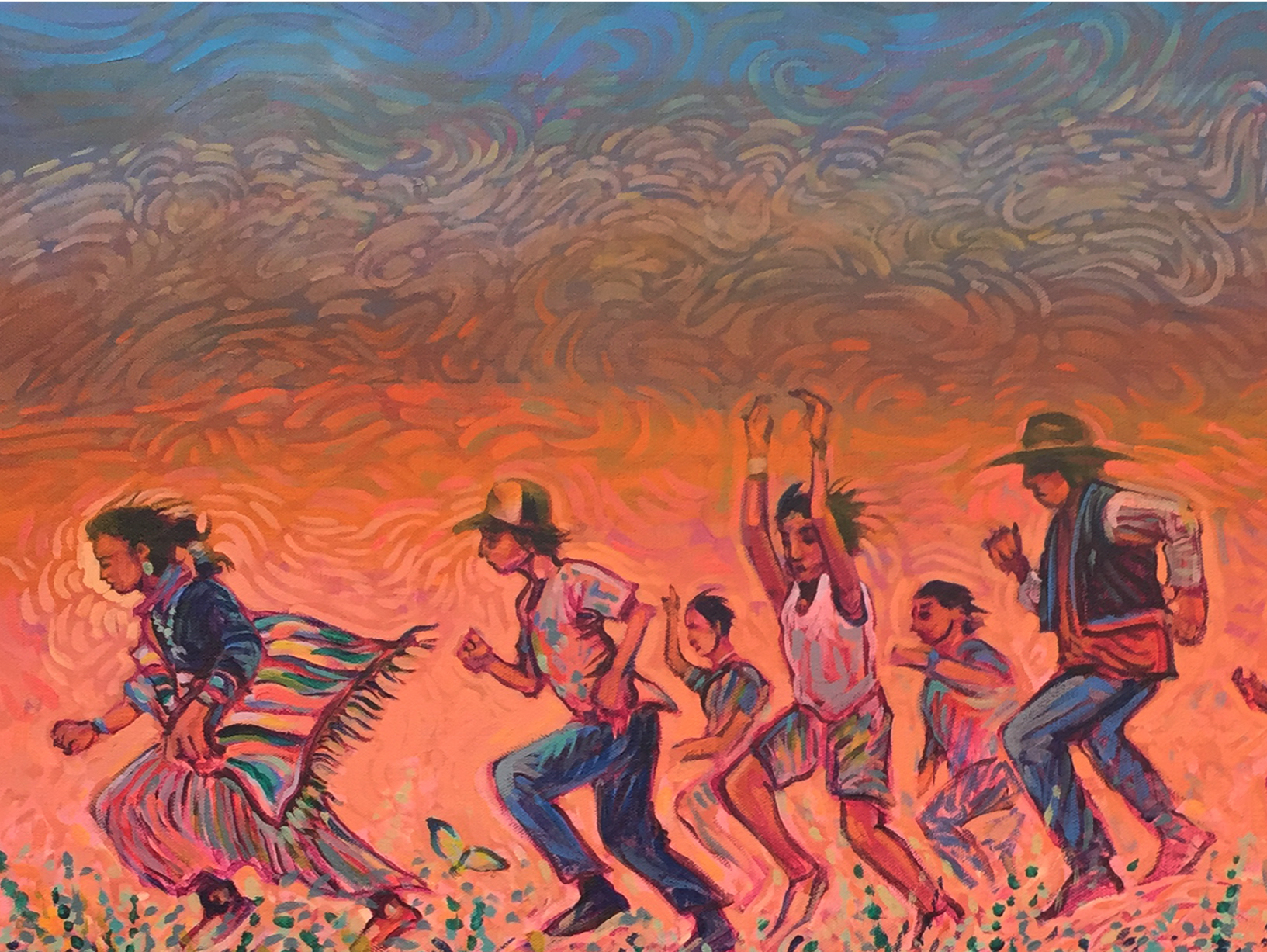

Both. My art documents pretty much everything I experience. I’ve also been blessed with very exciting dreams, which I tap into. Sometimes, I just can’t wait to go to sleep and enter that world. Also, in my culture, a dream is a powerful communication: you are actually living that reality in another space.

When I was living in the Bay Area, I started writing my dreams down. That’s how I became my own medicine man and kept my nightmares at bay; it’s also when I learned how to really write. Now I love both mediums, and I think they complement each other.

I had my own column for nine and a half years in a local Flagstaff newspaper. It was wonderful. I could talk about anything I wanted. A lot of the articles were a continuation of seeing the world through my eyes and the culture I was raised in—but using vocabulary instead of paint strokes.

Is point of view important to you when you’re painting?

Very much so. Because that’s how dreams work. I also like drama: the canvas is my stage. A lot of that is because I’m a big fan of comic books. I learned a lot about drawing individuals and actions, and how things can be seen from various angles, from comic books of old—DC, Marvel, and Gold Key. My paintings are all about pulling back the curtain and sharing the view from a stage. I’m basically an illustrator posing as a painter.

Who are your artistic heroes?

I admire artists like Winslow Homer and Norman Rockwell, as well as many comic book illustrators, who I made my teachers of sorts. An illustrator named Neal Adams, who did work for DC, is fantastic. He could just delineate the superhero body and give perspective like nobody’s business. Joe Kubert, another DC illustrator who did a lot of

Sgt. Rock, has a style that is fairly loose, wild, and beautiful but also adds so much information with spare detail.

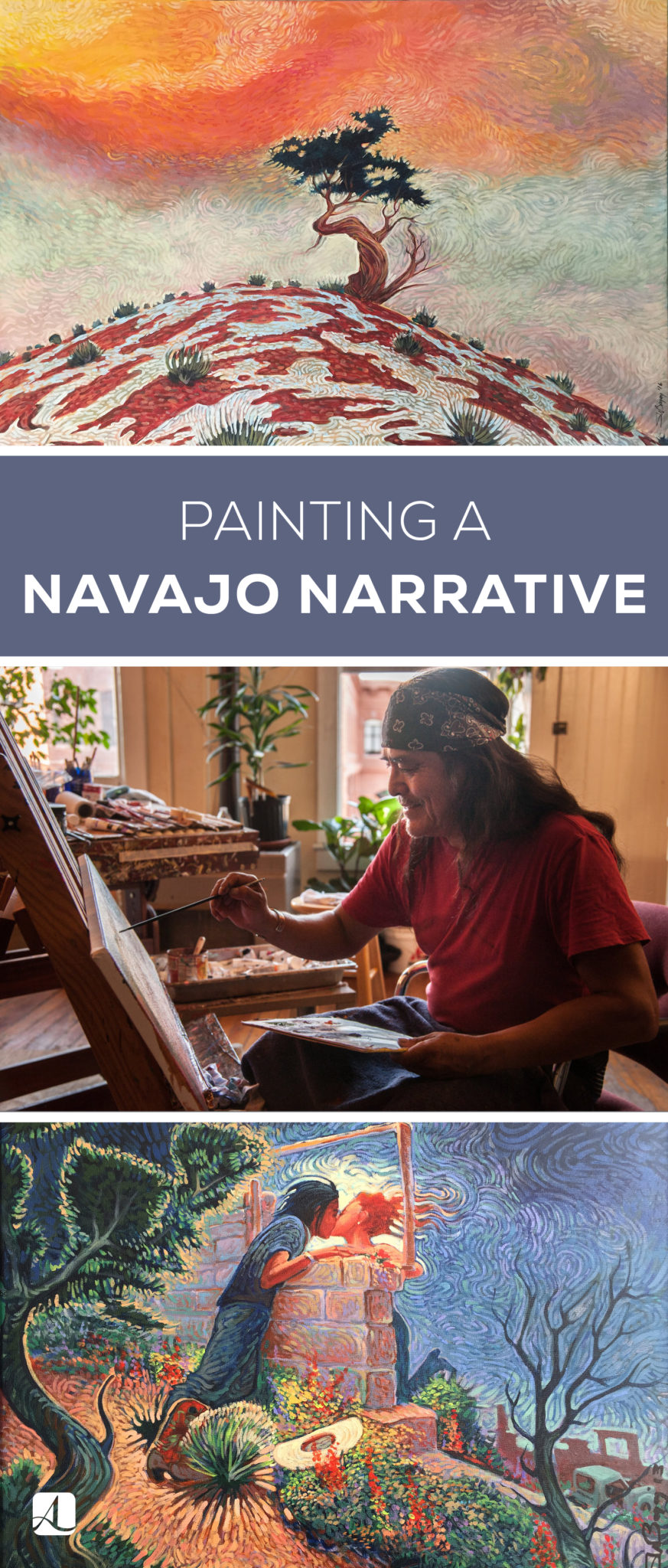

Your artwork includes many swirling lines. What do they mean to you?

I come from a family of spiritual artists, so my artwork is never done in a vacuum. Navajo healing chants offer an amazing healing journey within, and that is what I try to see when I paint. All the strokes, circles, lines, squiggles, curlicues, dots, and slashes I use are part of a visual chant through the spirit world. They are syllables, which lead to words, then to sentences, paragraphs, and, finally, to these ancient prayers. I have around thirty-one little marks that are alphabets in my painting, and I use them in every one of my works.

Tell us about the inside-versus-outside dynamic in your art:

When you’re raised in a hogan, you primarily stay there at night. Other than that, you’re outside in the mesas and canyons. So my world has always been mostly outside.

Being inside is very powerful, too, because it’s a place for dreaming, ceremonies, healing, and birthing. I do occasional inside images, but I think there’s an element of claustrophobia I want to bust out of—so I leave an opening, an escape for the viewer to get out.

I got this idea from the great Navajo rugs of old. In the beautiful patterns, the women include a line that goes all the way out to the edge. This is called a spirit break, which is where you release your creative spirit as a human. It allows you to go out and create even bigger and more beautiful things. They say if you don’t leave this line, you’ll weave yourself into one pattern and could get stuck.

What else do you like to do?

I still do a lot of outdoor things. I go home to see my brother and mother out on the reservation a hundred miles from where I’m living now. Every week, I spend time out there reliving my childhood by hauling firewood and water, riding horses, working with livestock, and planting corn. I’m usually with my kids or younger people, showing them that the way I grew up is a valid life.

I’m also illustrating another children’s book for Random House. I’ve had other offers in the publishing world come through, but I must make smart decisions. A lot of times, I’ll even run an offer past my people. I’m also a film buff, and I act. I did a movie called Monster Slayer, which was based on a Navajo creation story, and a love story, Alex & Jaime. I’ve turned down other film offers because the content didn’t hold true to Navajo life.

Do you think you’ll ever stop painting?

I can’t imagine moving on to something else. Painting is very important to me, a beautiful addiction, and I love it.

For more info, visit modernwestfineart.com/shonto-begay or follow Shonto on Instagram @shontobegay