Rare Air: The Udvar-Hazy Center

On December 17, 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright changed history: thanks to abundant planning, trial and error, and ingenuity, they became the first people to fly a plane. The brothers were airborne for 120 feet over the course of twelve historic seconds in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

Almost exactly a century later and 275 miles north of Kitty Hawk, near Washington Dulles International Airport in Chantilly, Virginia, the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center opened as a means to honor and display such historic feats of flight. Much like the National Air and Space Museum’s location on the National Mall in Washington, DC, the Udvar-Hazy Center plays an important role in preserving air and space history, being the storehouse for more than 2,800 aviation artifacts, 1,000 space artifacts (including 195 aircraft and 150 spacecraft and satellites), and 40 pieces of art. Over 200,000 people visited the center in the first two weeks after it opened in 2003, and it quickly became one of Virginia’s leading attractions. Today, the Udvar-Hazy Center welcomes over 1.5 million people a year.

It was the culmination of over fifteen years of lobbying, planning, and effort to get the center opened—and to solve a national storage problem. America had enjoyed a long history as an air and space pioneer, and it had accumulated a massive number of artifacts from its missions. The Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum was built in Washington, DC, in 1976 to display such artifacts. However, because of its relatively modest size (161,000 square feet), it could only share a portion of the historical treasures with the public.

So a second location had to be considered. Starting the next year, plans were put in motion to build a larger facility in close proximity to the original, which would make transporting the aircraft and spacecraft more feasible and cost-effective, as they wouldn’t have to be disassembled. One hundred acres south of Dulles International was secured, and construction of what was then called the Dulles Annex began in 1993. An entirely privately funded endeavor, it was renamed the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in honor of the executive of a global aircraft leasing company who contributed $65 million to help establish the center.

The Udvar-Hazy Center certainly achieved its purpose of expanding on the Smithsonian’s footprint dedicated to air and space. The center spans over five blocks and possesses over three-quarters of a million square feet—more than quadruple the space of the original. As such, it is home to an amazing collection of the country’s aviation and aeronautics marvels and other artifacts, all of which it acquires from a wide variety of sources, including the military, NASA, and private owners.

The center’s primary space is divided into two huge hangars: the eighty-foot-high James S. McDonnell Space Hangar and the ten-story-high, three-hundred-yard-long Boeing Aviation Hangar, the latter of which is particularly awe-inspiring. “When visitors enter our Boeing Aviation Hangar, the first word spoken for many of them is ‘Wow!’” says Amy Stamm, public affairs specialist for the Air and Space Museum. “In the aviation hangar, aircraft are displayed at three levels—two levels suspended from the building’s huge trusses and a third level on the floor. Most of the suspended aircraft have been hung in their typical flight maneuvers.”

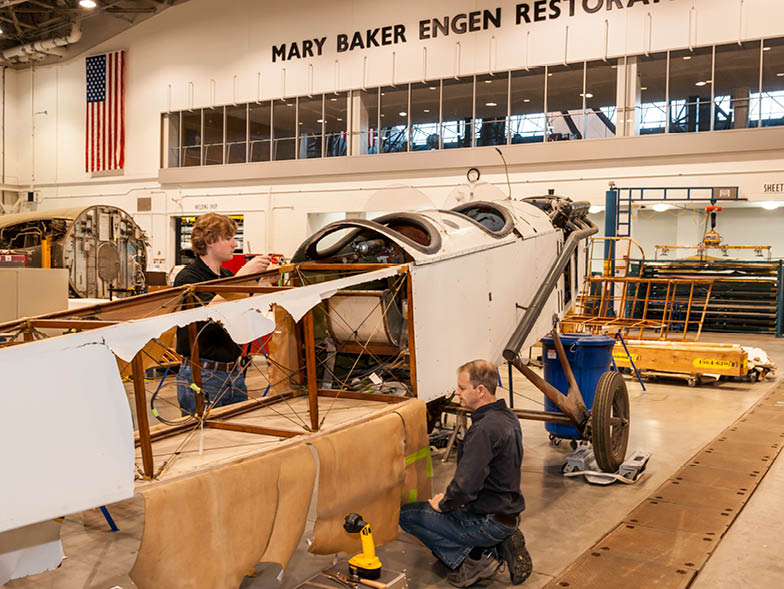

If you’re interested in massive flying machines or American aviation and space history, you’re like a kid in a candy store here, as there’s a virtual who’s who on display at both hangars. “Some of our most popular spacecraft and aircraft include the space shuttle Discovery, which flew the most missions of any space shuttle; the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird, the world’s fastest jet-propelled aircraft; and the Air France Concorde, the first supersonic airliner to enter service, which flew passengers across the Atlantic at twice the speed of sound for over twenty-five years,” Stamm says. She notes that visitors can also enjoy watching planes land at Dulles Airport from the Donald D. Engen Observation Tower and watch restoration work in progress from the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar overlook.

Over fifteen specialists ply their trade at the Udvar-Hazy Center, carefully ensuring that the artifacts are preserved to pristine condition while staying true to their original form. Of course, doing so takes a lot of skill, effort, and dedication—making for a fascinating experience to observe from the overlook and leading to an appreciation for the work behind each of these artifacts.

This kind of work, however, can present daunting challenges for those involved. “For us, challenges come in many forms,” says Robert Mawhinney, museum specialist in the Preservation and Restoration Unit. “It could be the extremely intricate press-formed wood fuselage of the World War I Albatros D.Va. that tests the skills and talent of any restorer, or the delicate preservation of the original 1918 fabric on the Caudron G-4, or the sheer size and scope of the Enola Gay restoration, which consumed more people hours than any other project. Every project presents a unique challenge—that’s part of the fun.”

As one can imagine, using only original parts when restoring decades-old machinery can sometimes cause a conundrum in those infrequent occasions when any are missing. “Most of our aircraft are complete and are disassembled for storage purposes, so it is fairly rare that we’re missing parts,” Mawhinney admits. “But when they are, we locate the parts any and every way we can. As part of the Smithsonian, we have contacts with museums and individuals around the world. We are fortunate that, oftentimes, when we do find something we need, individuals are apt to donate the item to our project. I’ve been told many times of the pride they feel helping complete one of the aircraft.”

Everyone at the Udvar-Hazy Center is also proud of its mission to inspire learning and excitement about aviation and space artifacts. “We like to say that the National Air and Space Museum is where ‘education takes flight,’” says Stamm. “We know that the future of aerospace is going to require brilliant minds in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math (or STEM), and we are committed to doing our part to inspire the next generation of innovators and explorers. We do so by telling the inspiring stories of aviation’s and space’s greatest feats, and also by making learning and STEM topics exciting and fun.

“To that end, we have a number of education programs, including Discovery Stations, where visitors can enjoy hands-on activities to learn the science or engineering principles behind flight. By helping visitors of all ages understand how a plane is able to take flight or how we can control the Curiosity rover on Mars all the way from Earth, we make the stories we’re telling come alive.”

For more info, visit airandspace.si.edu/udvar-hazy-center

As one can imagine, using only original parts when restoring decades-old machinery can sometimes cause a conundrum in those infrequent occasions when any are missing. “Most of our aircraft are complete and are disassembled for storage purposes, so it is fairly rare that we’re missing parts,” Mawhinney admits. “But when they are, we locate the parts any and every way we can. As part of the Smithsonian, we have contacts with museums and individuals around the world. We are fortunate that, oftentimes, when we do find something we need, individuals are apt to donate the item to our project. I’ve been told many times of the pride they feel helping complete one of the aircraft.”

Everyone at the Udvar-Hazy Center is also proud of its mission to inspire learning and excitement about aviation and space artifacts. “We like to say that the National Air and Space Museum is where ‘education takes flight,’” says Stamm. “We know that the future of aerospace is going to require brilliant minds in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math (or STEM), and we are committed to doing our part to inspire the next generation of innovators and explorers. We do so by telling the inspiring stories of aviation’s and space’s greatest feats, and also by making learning and STEM topics exciting and fun.

“To that end, we have a number of education programs, including Discovery Stations, where visitors can enjoy hands-on activities to learn the science or engineering principles behind flight. By helping visitors of all ages understand how a plane is able to take flight or how we can control the Curiosity rover on Mars all the way from Earth, we make the stories we’re telling come alive.”

For more info, visit airandspace.si.edu/udvar-hazy-center