Brian Mock’s Metal Marvels

Artwork by Brian Mock

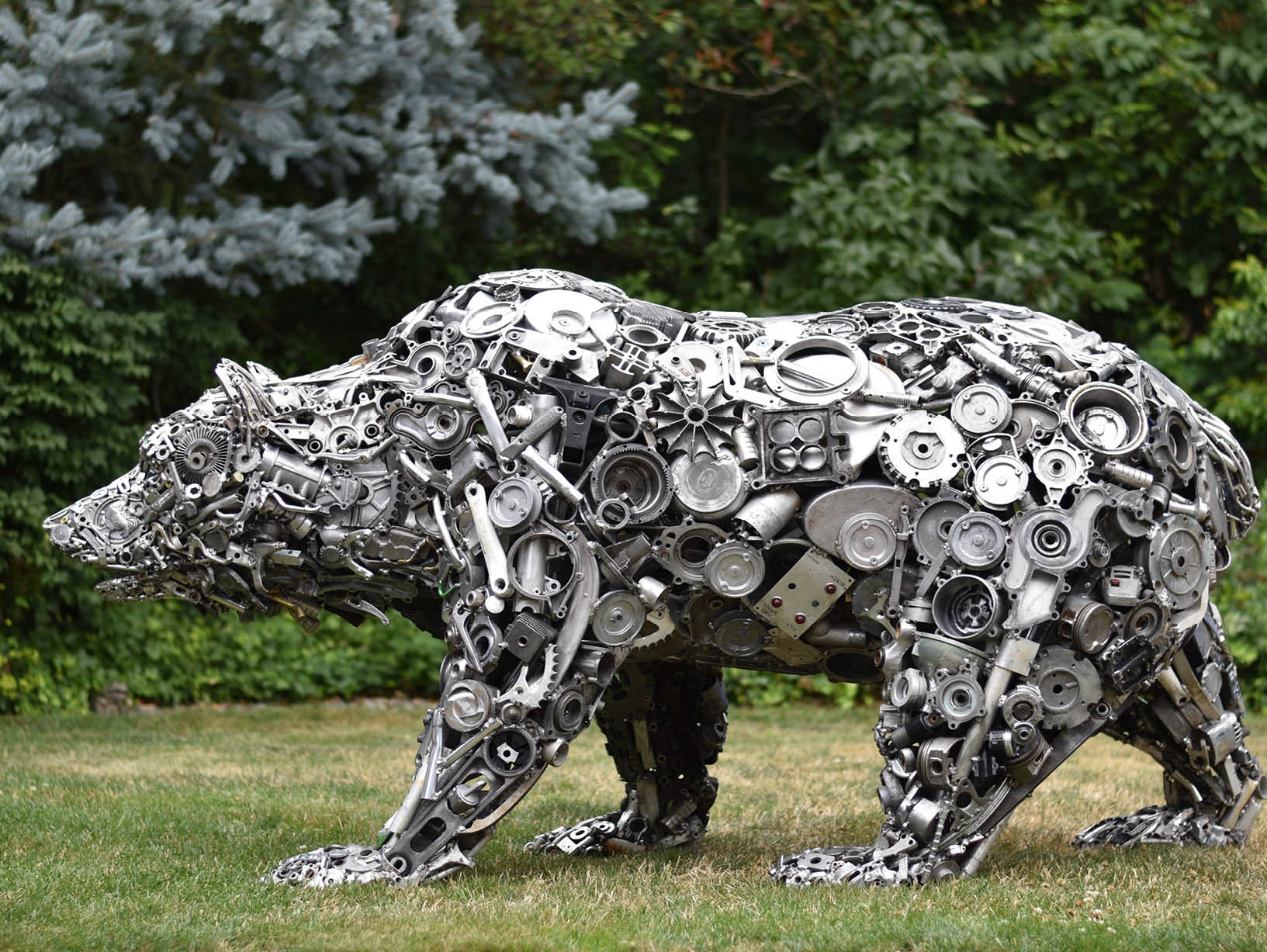

“Heavy metal” has a different meaning for artist Brian Mock, who transforms scrap materials into life-like sculptures. The self-described Metal Evolutionist talks about how he found his life’s work in this medium and its unique challenges and rewards.

Tell us about your art background:

I grew up outside Portland, Oregon. School never interested me much, but art always did. I loved doodling as a kid and spent many hours drawing, painting, and woodworking as a young adult. I just liked the process of creating.

Have you always thought outside the box when it comes to art?

Yes. Part of my creative process has always been figuring out how to make something from whatever is on hand, which forces you to think outside the box a lot. I used to make my drawing pads out of scrap paper I collected from trash bins at the printshop where my dad worked and bird feeders from broken fence boards I’d find on the side of the road.

Was metal sculpting your vision all along, or did you experience an “aha!” moment that led you down this path?

For me, metal sculpting was more like a happy accident. I had some minor success with selling my woodwork— car sculptures, bird feeders, and wine boxes—and thought it’d be fun to incorporate some metal embellishments into the work. So I taught myself to weld, not knowing that I’d have a natural knack for it and enjoy the process so much.

What is your process? Where do you get the parts for your sculptures?

I always research a subject before I sculpt it. If it’s an animal, I gather lots of images from different angles, and then I draw out a rough sketch of what I plan to make. I spend a lot of time sorting and sifting through materials, too. Most of the metal I’ve collected over the years has come from the scrap bins of machine shops, auto shops, and recycling centers. I’ve also received countless donations from generous people cleaning out their families’ garages or basements.

Tell us about the tools of your trade:

I use a MIG wire-feed welder for the welding. MIG welding, or gas metal arc welding, heats the metal by sending a high-current electric arc between the pieces of metal to be joined and an electrode, which in this case is a consumable spool of wire that’s continuously fed through the welder. I also use countless other tools, such as cutting discs, grinders, power tools, hammers, and an anvil, and I’ve modified many of them to meet my specific needs.

What does your shop look like?

Even though I’ve basically accumulated my own personal scrapyard, my workshop is actually very neat and organized. When people visit the shop, they’re often surprised by how tidy it is—I think they expect to see me literally working out of a junk heap. But most of the material is contained in bins and kept on shelving in my twenty-by-twenty storage structure.

How did animals become the subject you’re known for?

The first animals I made were dogs because Portland is a very dog-friendly city. People loved them and started commissioning me to sculpt their own dogs, and then other pets, and eventually their favorite animals—which is great, because I love animals and enjoy crafting them.

Your sculptures have such amazing detail. What techniques do you use to achieve this?

Thank you. I do spend a lot of time trying to get details right. I think that’s what makes sculptures like animals truly come to life—when I can achieve the right shape of a nostril or a muscle. I keep an inspiration board hanging in my shop for whatever I’m working on to refer to again and again until I’m happy with the details.

As someone who makes masterpieces through upcycling, what does recycling mean to you?

Recycling has always been a big part of my life, since it goes hand in hand with my resourceful nature. I even reuse the sweepings from the shop floor to create small sculptures. In fact, the term Metal Evolutionist came to mind as I was literally watching the metal I worked with evolve from one thing (a nut or a screw) into something completely different (a dog or a lion). So it felt like a fitting title. Over the years, I feel very fortunate to have created not just a lifestyle but an entire profession around it.

Which has been your largest sculpture to date?

It’d be a tie between the ten-foot Paul Revere on his horse at the Revere Hotel in Boston and the life-sized grizzly bear. Both were big undertakings in different ways. I ended up making the Paul Revere sculpture in five different sections that I welded together onsite so the sculpture could fit through the hotel’s front door. And the grizzly was made entirely out of aluminum, unlike my other works, which are mixed, mostly ferrous metals.

How heavy are your figures? Is creating, delivering, and displaying them difficult?

Medium-sized dogs weigh about a hundred pounds, and large-scale sculptures can weigh anywhere from four hundred to one thousand pounds. This does make logistics difficult at times. I have a hydraulic lift table, which can raise and lower a sculpture as I’m working on it, and a very patient wife, who helps me muscle the sculptures around for photo shoots. Many of my clients use their own freight services for shipping, but I’ve established good relationships with a couple freight drivers that I can count on to pick up my crated work when clients don’t have their own. I also custom-build all my own wooden shipping crates.

Who are your primary clients?

Most of my business comes from corporate clients, largely in the hospitality industry, or from private collectors, and it’s almost all

commissioned. I actually can’t remember the last time I made a sculpture just for fun, which is a good problem to have for my business but can sometimes feel constraining as an artist. The positives definitely outweigh the negatives, though—I like listening to clients’ ideas and then bringing them to life. Plus, I get to make a living doing what I love, and there’s nothing better than that.

Which sculptures are you most proud of? Is it ever tough to let them go?

One that comes to mind is Crouching Man, an installation I did for the Hotel Monaco in Washington, DC, because I feel like I was really able to capture the mood and edginess of the piece the client was looking for. I was more attached to my sculptures in the beginning because I was doing fewer commissions and making them more for myself, unsure if they’d even sell. Now, doing commissions, I start the projects knowing that they already belong to someone else, so they’re easier to let go of. I just make sure to take a lot of good photos!

What’s next?

I have some neat installation projects coming up, including a seven-and-a-half-foot guitar for the Hard Rock Hotel in Dublin and a large wine bottle for a winery in California’s Napa Valley. The long-term plan is to keep accepting new challenges that push and inspire me to grow as an artist.

For more info, visit brianmock.com.