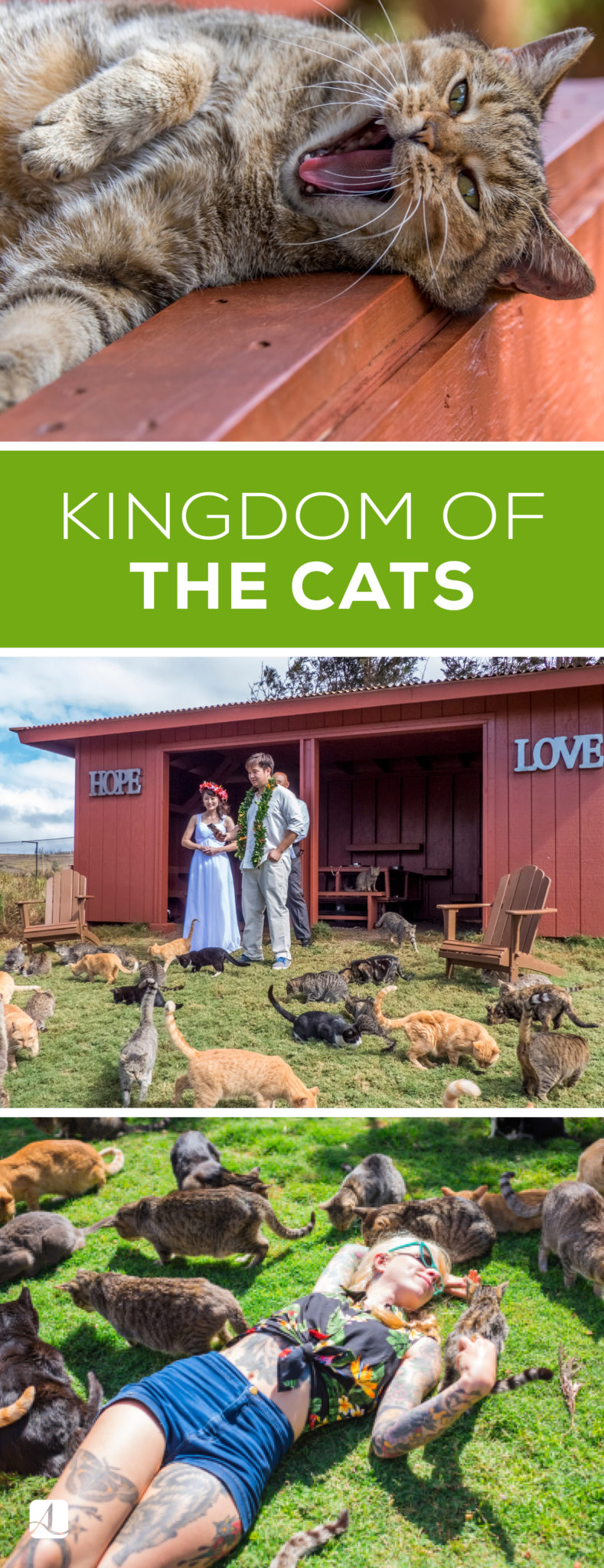

Kingdom of the Cats

photography by Lanai Cat Sanctuary

Throughout history, people have been crazy about cats. The ancient Egyptians worshipped them. Famed American writers Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway both had many cats, and the latter’s home/museum still has approximately fifty of his pets’ descendants on the premises. Queen’s Freddie Mercury wrote a song about one of his cats. Today, millions of Americans have them in their homes.

All these friends of felines would be happy to discover that there’s a cat paradise in … well, paradise. The Lanai Cat Sanctuary was founded in 2004 by cat lover Kathy Carroll, who sought to shelter the many free-roaming cats on Lanai—the smallest inhabited Hawaiian island, with about 3,000 residents. As years went by and the island became more and more overpopulated with cats, larger facilities were needed. The sanctuary moved to its current location in 2009, and today it has over six hundred cats and recently expanded to have an 1,100-cat capacity.

“The feral cat overpopulation is a really hot topic, especially in Hawaii,” says Keoni Vaughn, the sanctuary’s executive director, who grew up in Oahu. “Cats reproduce at a very alarming rate. Also, the weather here’s great year round—so it’s a perfect storm for feral cats to breed. And we don’t have predators that, in most places, keep cat overpopulation to a minimum. Mostly, though, this is a human issue. Back in the day, people would let their cats out, which weren’t spayed or neutered, and they multiplied. And this is all recent: pets weren’t even allowed on Lanai until the mid-nineties.”

Life on Lanai

Vaughn has led the charge to make Lanai Cat Sanctuary a must-see destination by capitalizing on the island’s—and the sanctuary’s—distinctiveness. “Lanai’s a unique environment,” he shares. “We don’t have any traffic lights. We have one gas station and a couple small grocery stores. But that makes it a close-knit place. People come to Lanai to totally get away. I think they’re really happy when they get here because it is so relaxed and

so secluded.”

But such seclusion can cause significant logistical challenges for a small nonprofit that relies heavily on donations. To get to the sanctuary, you can take a ferry from Maui and then a half-hour shuttle or cab ride, or you can fly in from Oahu and then commute to the sanctuary. And good luck finding driving directions. “There’s no physical address for the cat sanctuary,” Vaughn admits. “If you google us, you’ll get 1 Kaupili Road; that’s something that I made up. We’re on agricultural land in the middle of nowhere.” He’s not kidding: the sanctuary has running water but no electricity or internet (although it’s planning to add them).

Nonetheless, people are flocking here: Vaughn says that when he started in 2014, around eight hundred people visited the sanctuary per year—but in 2019, it welcomed upwards of 14,000 visitors to see the well-cared-for cats.

Saving Cats—And Birds

When you visit the Lanai Cat Sanctuary (which is open 365 days a year), you’ll find happy cats lounging virtually everywhere. In the main area, which has 30,000 square feet, you’ll find over five hundred felines. Another recently built area includes senior centers for older cats to live out their sunset years.

For the cats to be this happy and healthy, magic has to happen behind the scenes—and caring for this many cats certainly requires a great deal of planning. “We go through about eighty-five pounds of cat food a day, which costs roughly $48,000 a year,” Vaughn says. “We barge it in, as well as all our medical supplies. We have eight people on staff, but we don’t have a vet on the island. So I fly in Dr. Eric Ako, a veterinarian in Oahu, and his two assistants twice a month, and he provides medical care to the cat sanctuary. He may see anywhere between thirty-five and forty-five cats in a seven- or eight-hour period.” In all, Vaughn estimates that the sanctuary spends about $750 per year per cat, which is still under the national average of around $1,100 a year.

The Lanai Cat Sanctuary also takes what Vaughn calls a “herd health” approach. When cats arrive, they are spayed or neutered, named, and microchipped, and bloodwork is done, all to ensure they’re all healthy and fixed before they return to the main population. There are also eight treatment centers, which allow workers to remove ill cats from the population, treat them, and reintroduce them once they’re healthy.

The sanctuary’s mission is to provide a safe, healthy haven for cats—but it’s also invaluable to another species on the island. Lanai is home to native and endangered ground-nesting birds, such as the ‘Ua‘u Kani and ‘Alae Ke‘oke‘o, which feral cats hunt. By relocating the overpopulated cats to this permanent, safe home, rather than euthanizing them, Vaughn says it’s a win-win

for both.

From Feral to Friendly

As much as the facility itself has been transformed, many of its inhabitants change even more—much to Vaughn’s surprise and delight. “I’ve been in the animal welfare industry about eighteen years. I always thought, ‘Once a feral cat, always a feral cat.’ Boy, was I wrong. These cats are truly feral—they were born in the wild and haven’t seen humans or had human interaction until our intervention. Ninety-five percent of the cats here are like this. Amazingly, because of the staff interaction and our visitors, around 40 percent of them become socialized. I always jokingly call our sanctuary the Fur Seasons because these cats aren’t dying to get out.” In fact, Vaughn adds, like clockwork, every morning there’s a welcoming committee of about forty to fifty cats that surround the gate where guests arrive.

The Lanai cats are available for adoption and about fifty get adopted each year; however, since interested people are usually on vacation, arrangements must be made. Once a cat is chosen for adoption, its health is checked and a counseling session takes place so the adopter understands the cat and the commitment needed. The sanctuary’s manager then makes the long journey to get the cat to the airport the following day.

There’s no adoption fee, either; the sanctuary asks that the adopting party cover the expenses to get their cat back home and that they keep their cat indoors. (However, don’t expect to easily return your cat if the adoption doesn’t work out; since Hawaii is one of the few places in the world without rabies, you’ll be charged around $1,500 and the process can take months.) Want to sponsor instead? For thirty dollars a month, you can be the remote “owner” of a cat at the sanctuary and get monthly updates about your pet.

Vaughn says that all this effort is worth it because of how happy it makes visitors and residents. “The two biggest compliments we get here are ‘It doesn’t feel like six hundred cats’ and ‘It doesn’t smell like six hundred cats,’ ” he shares, with a laugh. “We take pride in the care of our cats, our sanctuary’s cleanliness, and the amount of space we provide. It’s not easy maintaining it, especially off the grid. But it’s really about creating that peaceful home experience for the cats and guest experience for visitors. Folks are meeting the cats, adopting the cats, and donating to keep us going. So we really appreciate every single person who walks through our doors.”

For more info, visit lanaicatsanctuary.org