Piecing Together a New Paradigm: Interview with Luke Haynes

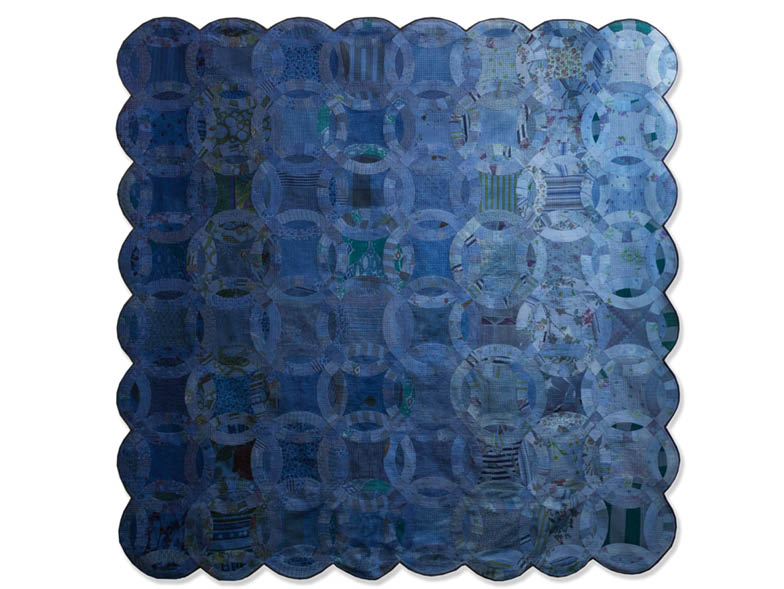

After a serendipitous quilting experiment in art school, artist Luke Haynes has devoted much of his career to redefining quilt-making for a modern age. He sources reclaimed textiles for his projects and explores the line between function and fine art.

What did your route to quilt-making look like?

I was born and raised across the American South. In 2002, when I was studying at an arts conservatory in North Carolina, I tried my hand at quilting, more out of curiosity than anything else. I made another quilt while I was studying architecture at Cooper Union in New York. After that, I was hooked. Ultimately, I felt that my schooling mostly helped inform me about technique and context for art and design.

How would you describe your approach to quilting? What parts of the tradition do you want to preserve, and what parts do you push?

For me, I have a few rules that I don’t break, and everything else is fair game for pushing boundaries. Rule One: ninety inches by ninety inches is the size of a quilt. I try some other sizes for studies, and there are plenty of historical examples of different-sized pieces, but I came to that size because it fits perfectly on my bed and therefore can uphold

the utility of the medium. Rule Two: a quilt is composed of fabric and thread. If I paint it, I would call it a painting, and if it’s another material, then it’s assemblage. Rule Three: a quilt has a depth of only three layers—top, batting, and back. If it starts to get too deep, it becomes a fabric sculpture.

You are known for depicting people on your quilts. What was the first portrait quilt you made? Where did that idea come from?

It was a portrait of me. I made it to see if I could, which was the driving force during my first many years of making. I was too shy to ask anyone else to sit for a photo to work from, so it was a default self-portrait.

Where do you source fabrics from?

Primarily from Goodwill or other used textile sellers.

How long does it take to make a quilt? What part of the process do you enjoy the most? And the least?

It takes anywhere between thirty hours and one thousand hours. It’s really dependent on the complexity and

my knowledge base of that pattern or method. I love the design phase and hate the binding and final finishing. By that time, I am so ready to be done.

I see that you travel with and photograph your quilts. What purpose does this serve?

My mission statement for the past few years is to talk about quilts as sculpture, and, to do that, they need to exist in different environments. It’s also a way for me to prove the usefulness of the objects rather than just the potential for high art.

Do you sell your quilts somewhere? Do you have a branch of art quilts and a branch of more utilitarian quilts, or are they in the same category for you?

I mostly sell to collectors who approach me. I have also started working with galleries again, like Blue Spiral 1 in Asheville, North Carolina. I have been thinking about making a range of utility quilts so I could get the price point lower and get more works into the hands of more people.

You also teach quilting classes. How much of your career is teaching versus making art?

Teaching is maybe 10 percent. I like to teach in a way that gives my students a skill set and also gives them permission to make their own experiments. It feels like giving back to the greater community, and it’s an amazing way to travel the world.

When you were living in Los Angeles, you built a fairly elaborate loft. Will you talk about this facet of your creativity?

I come from an architecture background and find that it comes out in as many ways as it can. I love lofts because they allow me to create an environment that suits my needs exactly. That is rare when most architecture is designed to fit as many potential buyers as possible.

I have the goal to do more architecture in the future and have started small here in Kansas City, Missouri, with flipping houses. I’ll see how big I can go.

What drew you to Kansas City?

I wanted to leave Los Angeles. I was done with the amount of work everything takes—from socializing to groceries to networking to dining out. I love the access to opportunities that larger cities afford, but the trade-off of traffic and expense became too much for me. Kansas City is, as of yet, undiscovered, which means that people have time to play, and priorities for community aren’t exclusively business-driven.

You’ve branched out into pottery. What inspired this exploration of ceramics? What does it offer you that quilting doesn’t?

I always have a few other hobbies and interests, but this is the first time one has consumed me as much as quilting has. Ceramics offers me a way to experiment that quilting doesn’t even come close to. In the first twelve months of trying ceramics, I made one thousand items. I really like that I can create functional items with a much smaller barrier to entry, both fiscally and time-wise. Also, it has some amazing similarities to quilting in that it’s a medium that isn’t always accepted into the pantheon of “art.” On the flip side, it has some really nice differences, like quilts are something often used in private, but ceramics are more likely to be used in a social setting.

How important is recognition to you? Would you rather be an artist’s artist but not well known in the public eye, or vice versa?

This is a question that I ponder a lot. I cherish the dialogue with peers and often find myself reaching out to others whose work I respect. Therefore, I would probably prefer to be known by the smaller community of makers I respect well instead of global recognition. The difficulty there is that what we know as success is measured by global reach, numbers of followers and likes, etc. The question becomes, “Do I prefer my conversations, or do I prefer to feel validated and successful?”

What drives you to create?

I want to know if it can be done. I often tell people that the reason I have been a quilter for so long is that the first one I made wasn’t very good, and I felt driven to make it better.

What projects are you currently working on?

I am working on a body of one hundred red clay cups, which is my self-imposed restriction in clay to learn form and technique and not get distracted by decoration. I am also working on one hundred quilts, where the fronts and backs are both made like the backs of my quilts. The backs of my quilts are made from sheets, so they are in essence an abstract study in the fabrics that are used privately and then discarded. I also love the idea that they won’t have a “top,” which pushes up against what we know “quilts” to be. This will be a project on the scale of installation once it gets completed and I find the perfect venues.

You are married to another artist. What is that dynamic like? Do you feel she’s influenced your work?

I love being married to another artist. It allows us to be supportive in ways that would otherwise be challenging, like scheduling. For example, she can take off and go to Japan for my shows, and I can go with her to market fairs. It’s also very helpful to hear input on my work from someone with the experience to look at the details.

If someone asked you what the meaning of life was, would you have an answer?

It depends on the day. Today, it’s to be present and really feel what I am feeling. And the idea that all of life is uncertain. It’s as easy to acclimate to success as it is to failure.

What is your vision for the next few years?

I want to expand my practice to include architecture—in whatever ways that may mean. I want to create spaces as well as objects. I am also working on finding new venues for my work and brainstorming ways to get my work in front of a larger global audience. I want to start a larger discussion about function and design and the way we live with and treat objects that maintain us as a species.

For more info, visit lukehaynes.com