Silver Linings Road Trip

Two days after my friend Tylor arrived in Seattle, the culmination of a cross-country road trip that began in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, he unexpectedly threw his back out. I heard a thump from the living room and then a forlorn moan, which turned out to be a mixture of pain and achievement—it had taken him twenty minutes to roll himself off the couch. The backpacking and hiking in the great Pacific Northwest he had planned morphed into story time in my apartment while binge-watching Perfect Strangers on Hulu. Tylor took it all in stride, as he always does, his find-the-silver-lining attitude a hallmark of his personality and a trait he’s consciously refined on his road trips.

If you’ve ever picked up a copy of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha or Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love, you’ll see a common thread of self-exploration through journeys and travel. Road trips are frequently romanticized in novels and films as the ultimate route to self-actualization or at least the answer to the protagonist’s problem. There is something about the forward movement of travel and breaking out of routine that gives the brain space to process life’s bigger questions.

Tylor has been taking these road trips for the past three years as much for the self-reflection as the sightseeing. His job (teaching woodworking to teenagers with special needs) can make for an intense school year. And the demands of managing a classroom do not leave him much time to reflect on his own questions about life, like “What kind of person do I want to be?” and “How do I want to move through the world?”

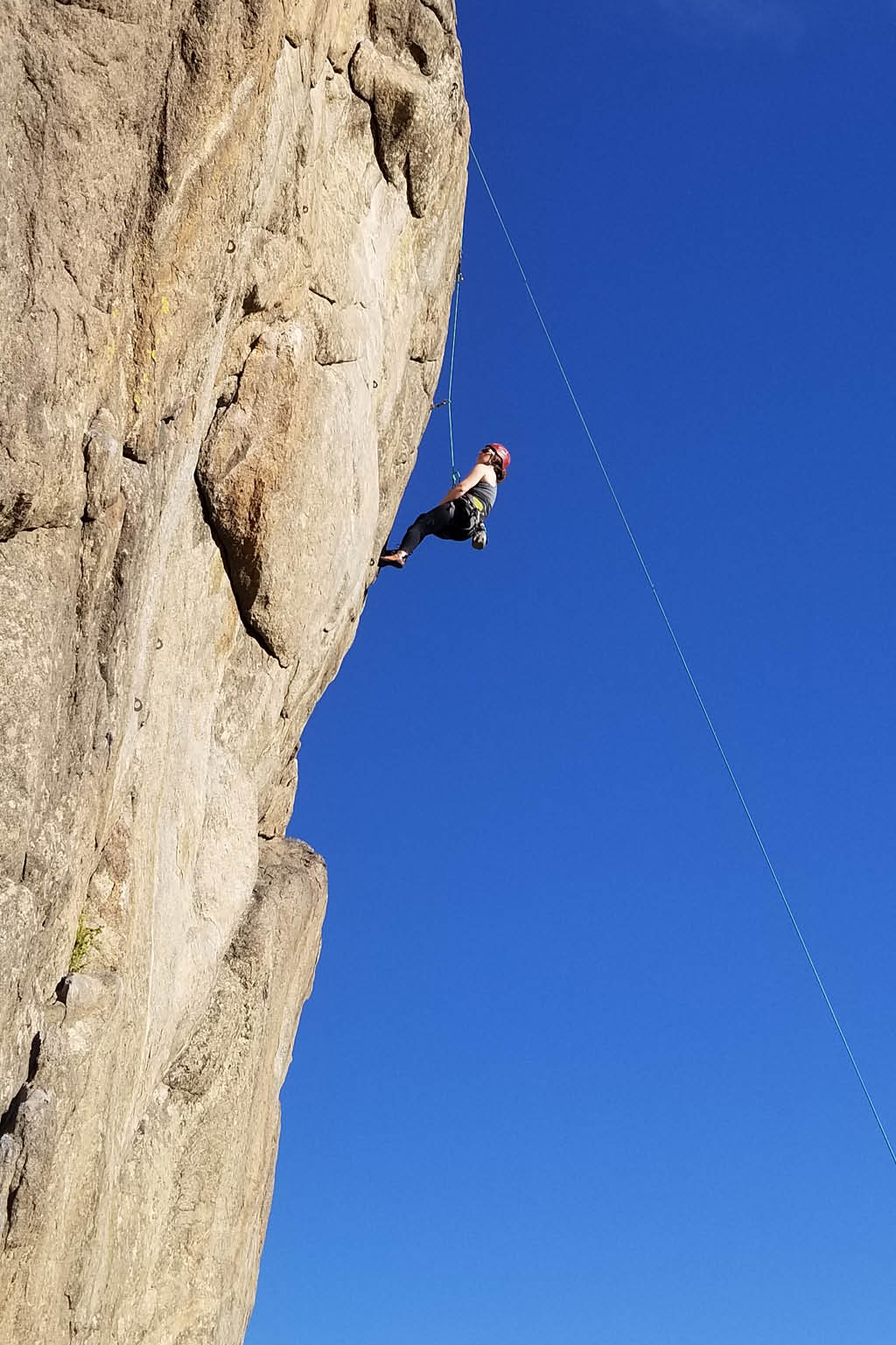

An important component of his most recent trip out west was outdoor rock climbing, a hobby he’s been carving out time for and pursuing for the past fifteen years. The trip from Carlisle to Seattle would include climbing stops in Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, and would take him almost two weeks. With a well-packed Mazda3 and his friend Lindsey in the passenger seat, he was all set to conquer the open road and the rocks.

After a grueling first day of driving and a one-night stopover in Jefferson City, Missouri, they arrived at the first climbing spot along Shelf Road in south-central Colorado. Part of the Gold Belt Tour Scenic and Historic Byway, Shelf Road was originally built as a stagecoach route to transport goods to and from Cripple Creek and Cañon City. This challenging drive is not for the faint of heart. The narrow, unpaved road features hairpin turns and steep drop-offs on one side and towering limestone on the other.

The Shelf Road climbing area boasts one thousand established routes, mostly bolted, meaning climbers can clip in to existing equipment, unlike trad climbing, which requires climbers to carry a rack of gear as they ascend.

Tylor and Lindsey chose to climb at the Gallery, a series of cliffs that line the canyon northwest of the Sand Gulch campground. His first climb of the day was aptly named Anguish and Fear, a sentiment he felt in his body—after being out of commission for a shoulder injury, it was his first outdoor climb in over three months.

As Tylor climbed, his mind wandered back to 2005, when he began working at a wilderness therapy company for adjudicated youth. Over the next nine years, he would lead camping trips, some for a month at a time, which included outdoor climbing. These trips had a profound effect on students and also made Tylor a very proficient and skilled outdoorsman. “It got me into outdoor adventure in a way that was purposeful and safe. It taught me how to take care of the resources we are using, how to camp efficiently and effectively, and how to minimize impact,” he explains.

It also taught less physical skills, like risk management, overcoming fear, problem solving, building trust, and communication. Tylor witnessed the changes in kids as they worked through their fears, learned to trust in the safety of their rope and the person below supporting them, and basked in the feeling of accomplishment at making it to the top or even a bit higher than they thought they could go. As he used the same breathing techniques he taught his students, Tylor found the fear dissipating and replaced with a renewed confidence.

After a night camping at Sand Gulch, the duo made a stop in Buena Vista, Colorado, to climb at Bob’s Rock, a small crag (or steep, jagged section of rock) with routes for all abilities. Climbing was beginning to feel more comfortable, and Tylor spent some time teaching Lindsey how to navigate some climbing holds. Then they headed to Salida to spend time with friends who rent a house there every summer. Smack-dab in the center of land-locked Colorado, Salida is home to the famous Arkansas River. And there’s no shortage of restaurant patios with a view of it. Hearty food is a necessity for refueling after a hard climb, and Tylor and his friends chowed down at the Boathouse underneath lime green umbrellas, enjoying the Yard Bird, one of its famous house-favorite fried chicken sandwiches.

The next day, they drove through Gunnison and Crested Butte and climbed at Taylor Canyon, a popular local spot. Finding public land that was not designated for cattle or grassland proved difficult, and they settled on a campground with running water, just short of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park. In the morning, they went to Black Canyon as spectators only. The canyon’s extremely deep and narrow dimensions make it a notoriously difficult spot with a high commitment grade (time investment) with some routes requiring a rappel into the canyon before being able to climb it. In addition, the majority of the routes are rated between 5.10 and 5.13. The Yosemite Decimal System organizes climbing into classes and grades. Class 1 would be walking on an established trail. Class 5 is where technical rock climbing begins. Once you hit 5.10, you enter the world of serious climber. And by the time you get to 5.13, you should be approaching Spider-Man status.

After admiring the superhero climbers, it was full steam ahead to Utah to climb at a popular area called Little Cottonwood Canyon, located twenty-five miles southeast of Salt Lake City. Though it’s named for the fact that it’s smaller than Big Cottonwood Canyon, located twenty minutes to the northeast, its four-hundred-foot granite rock faces are nothing to scoff at. It also has a really well-maintained and clearly marked trail system, making it more user friendly than many other climbing locales.

After staying with friends, the duo drove north just over the Utah-Idaho border to City of Rocks, considered a mecca for climbing. Routes have clever names like Wheat Thin and Muffin Top. “I led a really fun route named Colossus,” Tylor remembers. “About three-quarters of the way up, I was in a hollowed-out section of the wall, almost like an upside-down bowl, and I had to make a high, blind move around a corner.” Tylor explains why he enjoys such challenges: “There’s always something new to learn, a new experience, a new route, a new way to move up the wall. And people are cheering you on regardless of your ability.”

A nine-hour drive took them west to Oregon to a place called Smith Rock State Park, a majestic park that sprawls across 650 acres. It was in this land of basalt and compressed volcanic ash, also known as welded tuff, that Alan Watts began hand-drilling bolts for sport-climbing into the rock faces in the 1980s. His dedication to creating safer and more accessible routes is a big part of why Smith Rock is known as the birthplace of sport climbing today.

Climbing ensued during the day, and, at night, Tylor and Lindsey found their way into the town of Bend, forty minutes mostly south, to check out live bands and local attractions. Tylor was smitten by the amount of pets, remarking, “There might have been more dogs than people!” They also snuck in a tour of McMenamins’ Old Saint Francis School, including a hunt for the elusive Broom Closet, a bar and café featuring classic blues music that is hidden beyond what appears to be a wall of brooms.

After dropping off his copilot at the airport in Portland, Tylor continued north to Washington, eventually camping in a hammock near the trailhead of Mount St. Helens. After a hike in the afternoon, he made his way to the city of Seattle, meeting up the next day with a Seattle local to tackle the Pinnacle Lake Trail off the Mountain Loop Highway near Granite Falls. Though not a long hike, its steepness makes it a challenging one, but it’s worth negotiating the sometimes root-laced trail for the views and a dip in the alpine lake.

If the road trip hadn’t given him enough time to muse about his inward journey, the next four days of forced couch-sitting offered plenty of time for my slightly less mobile friend to gain clarity. He remarked about how easy it was to be present during the trip and how difficult that can be back home when he’s stressed about work and worried about his students. “I found joy in the little things, like the way the light hit the rocks or how the light changed depending on the time of day. I’d look at the clouds in amazement,” he says. “The trip gave me time to reflect on my job as a teacher and to appreciate the opportunities that come from it.” And though he literally couldn’t move for a couple of days, I saw my silly, thoughtful friend head back east lighter and more determined to keep searching for the silver linings of life.

For more info, visit nps.gov and mountainproject.com