The Art and Heart of Soil

Soil scientist Karen Vaughan combines her love of color, soil, and education to create watercolor paints and new pathways to learning.

When something is part of our environment for a long time, we often stop noticing it. This is why people rearrange their furniture and begin to see their house as new again or return from a weekend of camping with a renewed appreciation for hot showers. Scientist Karen Vaughan feels the same way about soil. “Maybe it’s because it’s below our feet or because soils are ubiquitous, but people don’t realize how important it is. You sort of forget about it because it’s everywhere.” Her mission in her roles as a scientist and a maker is to bring awareness to the beauty and wonder of soil.

Vaughan grew up in Rhode Island near the ocean, and she remembers frequenting the beach to get four-dollar lobsters straight off the boat. Her education and career took her all over the country, including Delaware, Florida, Maryland, Idaho, Utah, and California. Now an associate professor at the University of Wyoming, Vaughan is inspired by the state’s rugged landscape. “Wyoming has influenced everything about my soil art practice,” she says. “It’s dry here and there isn’t much vegetation covering the ground, so people can go out and see the quote-unquote Badlands. I use the quotes because they aren’t bad lands. They’re amazing lands. They may not be doing what you want them to do in terms of growing lush vegetation, but they’re salty and barren and beautiful.”

It’s no wonder Vaughan is enamored of soil—her research background is in wetland soils, mineralogy, and pedology. If you’re unfamiliar with the term, pedology is the study of soil formation, meaning it looks at how climate, organisms, relief (like slope and aspect), parent materials (the geologic or organic precursors to soil), and time influence how soil forms across a landscape. In addition to studying soil, Vaughan says she enjoys creating art: “I love doing things with my hands. I love to weave and knit. I like the feel of natural fibers. So I started creating soil profiles by felting or weaving tapestries of them, and then I started dyeing those fibers with natural materials.”

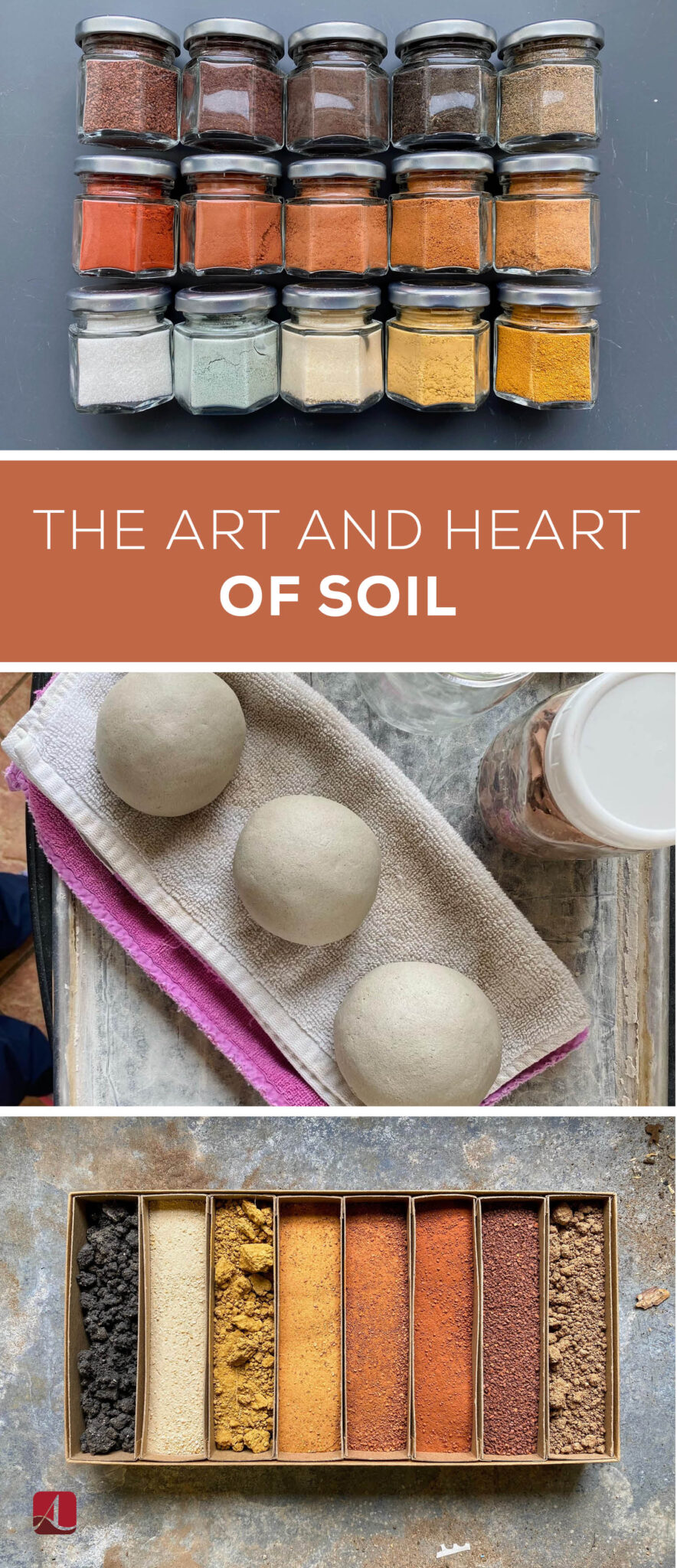

Vaughan’s fascination with soil colors stems from her work as a pedologist. Color is one of the tools soil scientists use to figure out what’s going on in the ecosystem below ground. For example, bright-red soil might point to iron concentrations. The artist and the scientist halves of Vaughan were intersecting and forming an idea. “I would see these absolutely beautiful soil colors and think ‘I wish everyone could see these.’ I get to dig these holes and be underground and spend time with soil, and other people don’t,” she shares. “So how could I take these colors and bring them out to the broader community? That was how these watercolors came about.”

She had acquired some beautiful soils from Wyoming and Utah and some bold soil colors from Tennessee and used them to create watercolors and crayons. “It was a natural partnership between soil and art,” Vaughan explains. The watercolors are all made with at least 50 percent soil—some are 100 percent. Vaughan collects the soil herself and then adds another natural pigment or a nontoxic synthetic pigment. The pigment and soil are then combined with a watercolor medium, which is her own proprietary mixture of water, acacia gum, vegetable glycerin, honey, and clove oil.

Her watercolor-making process uses a combination of scientific principles and patience. Once Vaughan finds the color of soil that she likes, she supersaturates it, essentially flooding it with water, and then mixes it up. Then it’s poured through a series of sieves designed to remove organic matter. Soils will settle depending on the surface area of the particles, so sand settles first, followed by silt, and finally clay. Using Stokes’ law (which gives the settling velocity of spherical particles), she calculates ninety seconds for the sand to settle. After pouring off the silt and clay, she’ll leave the jar overnight to let the water separate out. Then the clay and silt are poured into a baking sheet to dry in the sun or the oven. Once it’s dry, the mixture is ground up with a mortar and pestle and mulled with the watercolor medium for a half hour to an hour.

Vaughan’s watercolors are a family endeavor. Her husband, Rob—also trained as a pedologist—cuts and carves all the wood palettes for the paints. And her two children help make boxes or package palettes. Each color name is inspired by a place or the mineral that’s responsible for the color. Early on, the packaging was minimal, but Vaughan’s innate desire to educate eventually kicked in, and she realized she was missing an opportunity to dispense valuable information. Now she includes well-designed info cards that walk customers through the soil and pigment and watercolor media so they know what they’re using.

It was the same goal of education that birthed Vaughan’s first Instagram account about soil science. She shared photos from research labs and courses she taught at the University of Wyoming, and she was amazed to have even a couple of thousand followers. A few years later, she teamed up with another soil science professor named Yamina Pressler to start a soil science education outreach and art organization. The handle they chose was @fortheloveofsoil. When her interest in soil-based watercolors grew, Vaughan started a new account, appropriately named @theartofsoil.

With over 96,000 followers, it has taken on a life of its own. “I was blown away by its success, how much joy I get out of it, and how much fun it is,” she admits. “I love seeing the community grow and ask interesting questions from their different backgrounds.” The people following the account, including pedologists, geologists, soil scientists, ecologists, artists, gardeners, and makers, vary widely. Vaughan is delighted by this, explaining, “It’s fascinating to me that people who are seemingly dissimilar in terms of their professional pursuits are developing relationships through this account.”

At her core, Vaughan is an educator, a leader, and the kind of person whose own excitement and interest in the natural world spills over and fills the cups of others. And she understands how sacred this planet is. “The way we frame ourselves as humans is so important,” she concludes. “Some of us think of ourselves as separate from the natural world, but every single thing we do makes an impact. There’s a lot of gloom and doom about the planet, but I prefer to think about actionable items. What can we do to make sure we’re doing the best for this planet and future generations? We’re all learning. We’re all figuring it out. We all want what’s best for this world; we just come at it from a different perspective.”

For more info, visit theartofsoil.com or @theartofsoil on Instagram