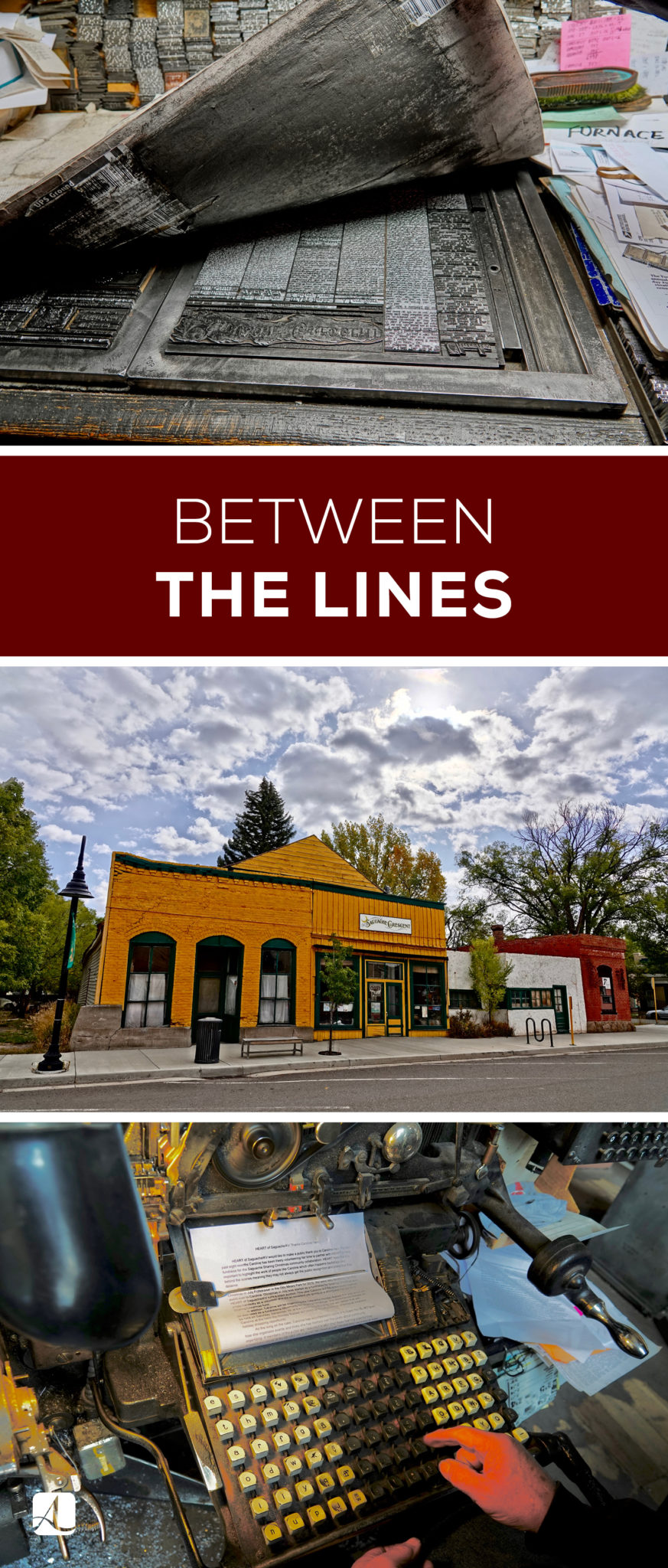

Between the Lines

Photography by Jeff Nye

On the corner of San Juan Avenue and Fourth Street in Saguache (pronounced Suh-WATCH), Colorado, stands a building the color of daffodils, with green trim and many windows, and if you tap on the glass, you might just get invited in. On most days, one can find Dean Coombs—the third-generation publisher of the Saguache Crescent—tinkering on a Linotype machine inside. The Crescent is the only Linotype newspaper in the country, and maybe even the world. Talking to Dean Coombs is like getting a history lesson and a tutorial on newspaper printing at the same time. Coombs has only lived away from Saguache for four years, making the sixty-eight-year-old newspaper publisher a de facto historian of sorts as well.

The Saguache Crescent has been a fixture in Saguache County for well over a century and has been in Coombs’s family since 1917, when his grandfather moved from New Mexico with his family to purchase the paper. His grandfather’s uncle had passed away, leaving an estate worth $12 million in 1914. The money was divided among a large family, but Coombs’s grandfather was able to buy the paper outright. And a couple years later, he purchased a Linotype, having printed previous editions of the paper by hand-setting type. Linotype machines were very expensive at the time, and most were owned by large papers, which the Saguache Crescent was not.

Saguache is a rural town of five hundred people, fifty miles from anything even resembling a large town. The main employer is the county, which provides government jobs as well as jobs for teachers. The other industry is, of course, agriculture, with some farming and a lot of ranching. In other words, the opportunities to make a living are not vast, and the paper offered a steady income for the family. After Coombs’s grandfather passed away in 1935, his grandmother ran the paper and his mother operated as editor, while his aunt set the type.

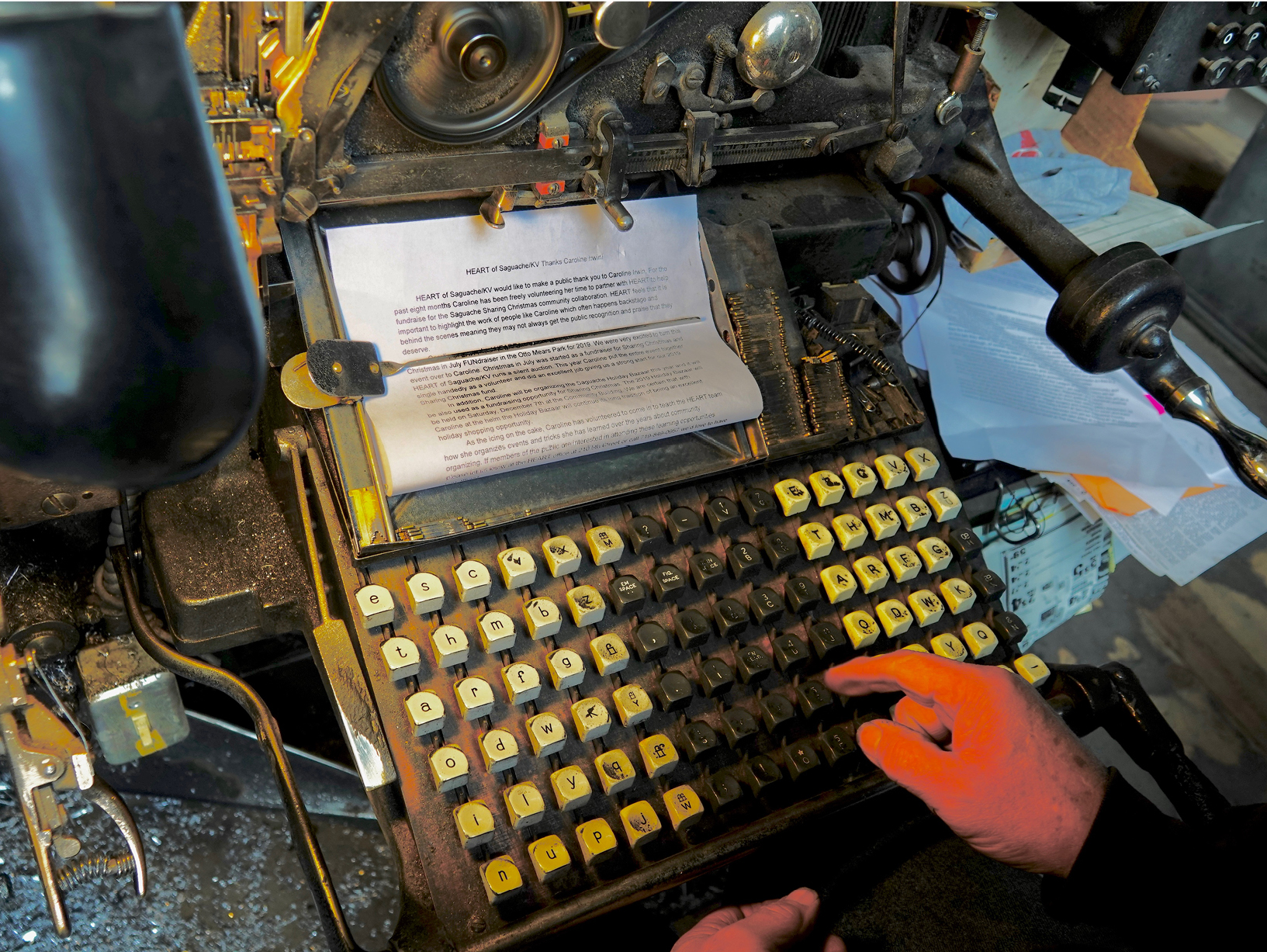

Hand-setting had been the only printing technology available from Gutenberg until 1886, when linotype was invented. Linotype was a form of mechanical typesetting, and it was four times faster than hand-setters. Hand-setting meant the movable metal type all had to be put back after it was used, and you also had to buy it. The Linotype made its own type, for just the price of lead. Coombs explains, “When you did a book, you set the book in handset and then you had to take the book apart. But once you set it in Linotype, you just put it away and then reprint it from that. It dropped the price of books tremendously and made newspapers bigger.”

When Coombs’s mother married, his father stepped into the role of printer, eventually purchasing a second Linotype for the business. “He got tired of waiting for my mother to get off the machine,” laughs Coombs. In 1971, they bought a second, used Linotype outright for $1,200, plus $1,000 to ship it from Denver. In addition to the newspaper, they also printed commercial-work jobs, making the second machine a solvent decision.

When Coombs’s father died of a heart attack the day after Christmas in 1978, it was twenty-six-year-old Dean who found himself suddenly the publisher of the Crescent. Already realizing college was not the place for him and having spent four years outside of Saguache doing odd jobs, Coombs was not afraid of hard work. “It’s harder to get out of the newspaper business than to stay in,” he explains. “We pushed on and put out the paper the day he died.” Coombs had to quickly learn the ins and outs of the Linotype machines now in his care. The mechanical machines are comprised of many moving parts and plenty of screws that can loosen to the point of stopping the machine. Says Coombs, “You don’t need an engineering degree. It’s mechanical. You stop and look.”

Linotypes begin with brass mats, short for matrices, which are anything you can make something out of, like molds. The machine lines up the matrices and puts them into a casting position, which injects molten lead into the molds. This results in what’s known as a slug, or an entire line of type—hence the name Linotype. By contrast, hand-setting was a tedious process, especially when it came to inserting tiny spacers between the letters and words to create the newspaper standard of justified text (meaning the paragraphs lined up on both the left and the right).

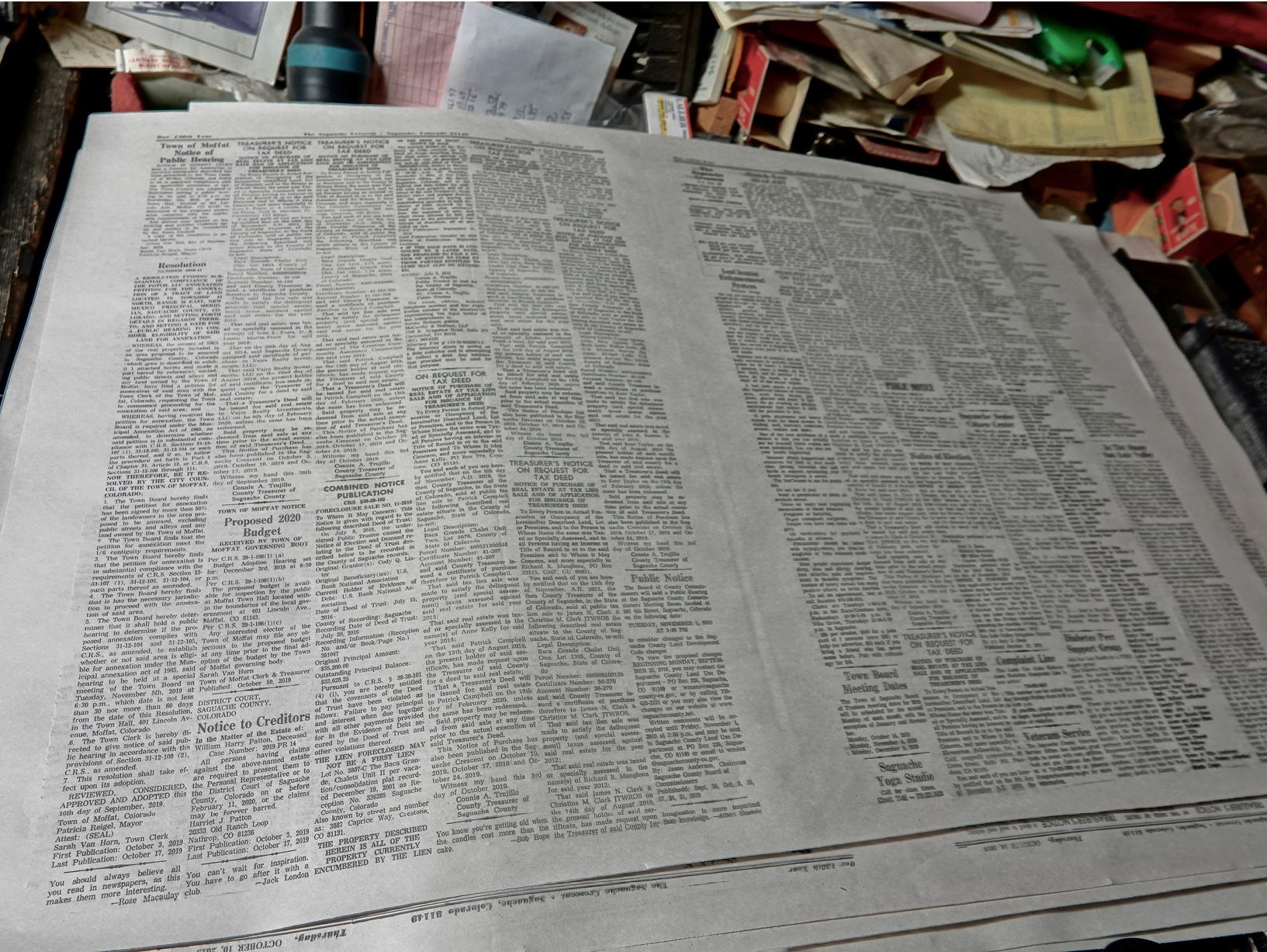

The Saguache Crescent is a four-page paper, which starts out as a 30” by 22” sheet and is then folded down to 15” by 22”. A single font is used for the text, though Coombs admits to a bit of a font habit, collecting 250 fonts for his own library. The paper mails every Wednesday, with a Thursday publication date. An in-county subscription costs just sixteen dollars for an entire year.

The majority of the income does not come from subscriptions, however. Saguache County has so much

private property, and with that comes frequent buying and selling. Tax sales are advertised in the paper, and then the titles must be printed as well. The county pays for the legal notifications to be printed.

The front page is news, but only good news, a tradition Coombs’s mother started and he’s upheld. The back page is ads and classifieds. The aforementioned legal publications take up one inside page, and the other offers general information, like a book sale listed by a museum or a quilting club announcing its meetings. The Crescent does not do any of its own reporting, but it does have some regular contributors, like the school principal as well as a man with a penchant for history articles. Coombs himself has only written one article during his tenure: an account of his own family’s history to commemorate their one hundredth anniversary of owning the Crescent.

He credits his stubborn personality and his distaste for change as assets when it comes to running the newspaper. There’s no pause in the newspaper business, especially a small, family-owned outfit, and one has to be committed.

“When my mom was alive, she was interviewed on television, and she said, ‘I don’t know. I just go to work.’ And I thought, ‘What a stupid answer that was.’ But twenty years later, you know, she’s actually right,” he concedes with a chuckle. It’s impossible to take a week off. He’s only missed one day of work, and that was on account of food poisoning. Living next door helps as well—you can’t beat the short commute.

Coombs has no plans to train someone to take over the newspaper, joking that there’s no one he dislikes enough to give the paper to. He hasn’t decided when he’ll retire, but he reckons there might be a million-dollar yard sale of equipment (and fonts!) involved. For now, he’s happy to have the shop to himself, waving the occasional tourists inside for an impromptu tour and a history lesson.

To send a letter to the Saguache Crescent:

Dean Coombs, P.O. Box 195

Saguache, Colorado 81149